Science News

A Busy Week in Space News

A Busy Week for Commercial Spaceflight

In the interest of safety, most manned spacecraft have featured a launch escape system—a small rocket tower atop the vehicle that, in the event of a catastrophic launch abort, would lift the crew capsule safely away from the main booster. The capsule could then parachute gently back to the ground.

(Such a contraption has been used only once in manned spaceflight, during the aborted 1983 launch of the Soyuz T-10-1 mission, scheduled to visit the Soviet Union’s Salyut 7 space station. When a malfunctioning fuel valve led to a fire in one of the Soyuz rocket boosters, the launch escape system lifted the separated capsule to 2,100 feet (about 640 meters), momentarily subjecting the cosmonauts to 20 times the pull of Earth’s gravity! But saving their lives. After parachuting to the ground, the crew settled their rattled nerves with cigarettes and vodka.)

On May 6—only a week after launching a satellite into orbit for Turkmenistan—SpaceX will simulate an emergency launch abort involving its crew-rated Dragon space capsule by firing an unpiloted mockup of the spacecraft from a test stand at Cape Canaveral. Instead the traditional launch tower, Dragon has rocket engines built into its sides—an economical “pusher” configuration that doesn’t require the additional weight and engineering of an escape tower designed to pull the capsule off the rocket (a.k.a. a “tractor” configuration). In addition, the integrated system makes escape capability available throughout the entire launch sequence and is not discarded at mid-launch, as during the Apollo missions. Eventually, SpaceX plans to use the same system for powered descent during a Dragon capsule’s return to Earth.

For the upcoming test, sensors inside a crash test dummy in the Dragon capsule will measure g-forces to help determine the survivability of the emergency launch procedure. Later, SpaceX will conduct a similar abort test while in flight—another step toward certifying the Dragon vehicle for human spaceflight, which SpaceX hopes to begin as early as 2017, launching crews into space from American soil.

In a surprise development in the commercial spaceflight arena (which is seemingly turning into a “battle of the billionaires”), Blue Origin, a company owned by Amazon.com’s Jeff Bezos, launched its bullet-shaped New Shepard spacecraft last Wednesday from Texas. Powered by Blue Origin’s own restartable, million-horsepower engine, the squat main booster lifted an unmanned space capsule to an altitude of 58 miles (93 kilometers), nearly clearing the internationally-accepted 62-mile (100-kilometer) boundary defining outer space. Although the main booster lost hydraulic fluid and was not recovered (it crashed), it is designed to make a vertical landing in a fashion similar to rival SpaceX’s Falcon 9R first stage, only completely under the control of onboard computers. Despite the failure of that aspect of the test flight, the dummy capsule parachuted safely to the ground, prompting Bezos to comment that “any astronauts on board would have had a very nice journey into space and a smooth return.” More test flights—including, presumably, booster recovery attempts—will take place this year, perhaps monthly, according to Blue Origin President Rob Meyerson.

New Shepard will be used primarily for space tourism, flying passengers just high enough to qualify as having reached outer space, then parachute them back to the ground, in direct competition with Sir Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic, which will execute a similar flightplan, but glide back to a runway landing on its winged SpaceShipTwo vehicle. Other spacecraft are being developed to exploit the space tourism market, although none are designed to take passengers into orbit. However, Blue Origin has stated its ultimate intention to fly crew and cargo to the International Space Station, like SpaceX, but in a larger rocket designed to reach orbit, called the Very Big Brother. –Bing Quock

Messenger’s Grand Finale

Yesterday, April 30 at 12:46 p.m. PST, NASA’s Messenger spacecraft crashed into the planet Mercury, ending its 10 years in space and its four-year mission orbiting the Solar System’s smallest planet.

Launched in August 2004, Messenger took a tour of the inner solar system before arriving at its target, using gravity assist from each of the flybys to gain speed while using the lowest possible amount of fuel. It was slingshot once around Earth, twice around Venus, and thrice around Mercury before settling into orbit in March 2011.

In slightly over four years, Messenger has mapped Mercury’s surface in detail, sending back over 270,000 images and 10 terabytes of scientific measurements and data. Its major discoveries include finding Mercury’s magnetic field to be bizarrely off-center, spotting water ice sheltered in shadowy polar craters, and uncovering evidence that Mercury’s core contracted far more than expected in its past.

The mission has certainly not been boring for the ground control team, who fought instrument malfunctions and other challenges caused by the planet’s close proximity to our active star. The Sun’s gravity has also nudged the craft closer to the planet, causing Messenger to rely on occasional “bumps” to maintain its orbit. However, fuel ran out last month, meaning the craft would inevitably lose altitude and crash to the surface. The team made the most of it, collecting as many images and as much data as possible before it plummeted.

The 1,130-pound (512-kiolgram), 10-foot (three-meter) long craft is estimated to have created a crater about 50 feet (15 meters) across near Mercury’s north pole. Telescopes watched the impact itself with good resolution, and Slooh.com hosted a live broadcast of the event.

Intentional “hard landings” are not uncommon ends to planetary exploration missions. In 2009, the LCROSS mission crashed into the south pole of the Moon to analyze dust kicked up by the impact. In 2003, Galileo plunged into Jupiter to study its atmosphere. Cassini, orbiting Saturn, will also likely end its mission by plummeting into the gas giant’s atmosphere.

The only other mission to previously visit Mercury was Mariner 10 in 1974 and 1975, completing three flybys. However, the closest planet to the Sun won’t be alone for too long. BepiColombo, a joint mission between the European Space Agency (ESA) and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), consists of twin orbiters and is slated to launch in 2017 with a 2024 arrival. –Elise Ricard

Getting closer…

NASA’s New Horizons mission is now only several million miles from Pluto. I say “only” because it started here on Earth nine years and almost three billion miles (five billion kilometers) ago. It’s getting closer every day and on July 14, it will reach its closest approach.

Over the next few months, Pluto will become clearer to those of us on Earth, too, as New Horizons snaps pictures during its approach. In fact, this week, NASA released extraordinary images of Pluto and its moon Charon that anticipate things to come. Brighter and darker regions are now evident, including a bright spot near the pole, revealing a potential polar ice cap.

“As we approach the Pluto system we are starting to see intriguing features such as a bright region near Pluto’s visible pole, starting the great scientific adventure to understand this enigmatic celestial object,” says NASA’s John Grunsfeld. “As we get closer, the excitement is building in our quest to unravel the mysteries of Pluto using data from New Horizons.”

“We can only imagine what surprises will be revealed when New Horizons passes approximately 7,800 miles (12,500 kilometers) above Pluto’s surface this summer,” echoes Hal Weaver, the mission’s project scientist at Johns Hopkins University. Stay tuned. –Molly Michelson

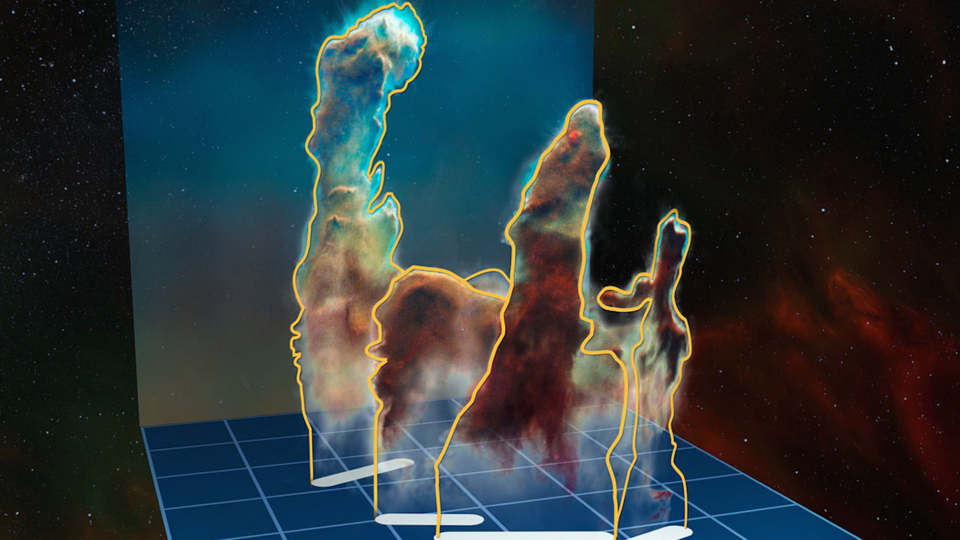

3D Nebulae

Space looks flat. Because of the Universe’s unimaginable vastness, everything lies so far away from our eyes on Earth that we can’t get a three-dimensional perspective on the phenomena that surround us. The Hubble Space Telescope may send back unbelievably gorgeous images, but they only show us how things look in two dimensions.

Astronomers use different techniques to tease out the third dimension in distant objects. One method relies on the slight shift in a wavelength of light emitted by a moving object, which basically tells us whether something is moving toward or away from us. This can reveal more than you might expect: the expansion of a nebula, for example, or the rotation of a star or the presence of an unseen planet.

A group of astronomers led by A.F. McLeod at the European Southern Observatory (ESO) in Garching, Germany, applied this technique to a well-known star-forming region. The famous “Pillars of Creation” image that garnered considerable attention in 1995 received a 20th-anniversary revamp in January, and now these ESO researchers have coupled the eye-catching image with 3D data about the Eagle Nebula in which it resides.

Measuring gas emission moving both toward and away from us allowed them to determine that the leftmost pillar is not only more distant but also tilted toward us. And the two pillars on the right of the image are tilted away from us, in the foreground. These results allowed the ESO team to create a short video that pivots around the pillars and reveals their 3D relationship.

Our telescopes may not take 3D images of distant objects, but at least astronomers have a powerful toolkit with which to add a new dimension to our understanding. –Ryan Wyatt

Mysterious X-ray from our Galactic Center

The center of our galaxy contains a puzzling population of stellar objects, with a high abundance of surprisingly young, relatively massive stars bound to the central supermassive black hole, and a more extended population of burnt-out stars (white dwarfs) and the remnants of a supernova. We have pieced together this picture based on observations of X-ray emissions over time.

This week astrophysicists Kerstin Perez, Fiona Harrison, and colleagues announced the detection of a new X-ray signal emitting from our galactic center, spotted by NASA’s Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR) telescope.

“We can see a completely new component of the center of our galaxy with NuSTAR's images,” Perez says. “Almost anything that can emit X-rays is in the galactic center. The area is crowded with low-energy X-ray sources, but their emission is very faint when you examine it at the energies that NuSTAR observes, so the new signal stands out… We can’t definitively explain the X-ray signal yet—it’s a mystery. More work needs to be done.”

The team offers four potential theories to explain the baffling X-ray glow, three of which involve different classes of stellar corpses. When stars die, they don’t always go quietly into the night. (As the press release’s headline reads, “NuSTAR Captures Possible ‘Screams’ from Zombie Stars.”)

According to one theory, pulsars could be at work. Pulsars are the collapsed remains of stars that exploded in supernova blasts. They can spin extremely fast and send out intense beams of radiation. As the pulsars spin, the beams sweep across the sky, sometimes intercepting Earth, like lighthouse beacons sweeping across the ocean.

“We may be witnessing the beacons of a hitherto hidden population of pulsars in the galactic center,” Harrison says. “This would mean there is something special about the environment in the very center of our galaxy.”

Other possible culprits include heavy-set stellar corpses called white dwarfs, the collapsed, burned-out remains of stars not massive enough to explode in supernovae. Because these white dwarfs are much denser than they were in their youth, they have stronger surface gravity and can produce higher-energy X-rays.

Another theory points to small black holes that slowly feed off their companion stars, radiating X-rays as material plummets down into their bottomless pits.

Alternatively, the source of the high-energy X-rays might not be stellar corpses at all, astronomers say, but rather cosmic rays. The cosmic rays might originate from the supermassive black hole at the center of the galaxy as it devours material. When the cosmic rays interact with surrounding, dense gas, they emit X-rays.

The team says they are planning more observations. Until then, theorists will be busy exploring the above scenarios or coming up with new models to explain what could be giving off the puzzling high-energy X-ray glow. –Molly Michelson

Image: ESO/M. Kornmesser