Science News

Fossil Treasures

March 20, 2014

by Molly Michelson

Fossils can tell us a lot about the past, but they also give us information for the future, according to new papers in PLoS ONE today.

Feathered dinosaurs in North America

Oviraptorosaurs are a group of feathered dinosaurs of Asia and North America dating from the Cretaceous period. Sadly, the North American record of these therapods has been lacking. Until today.

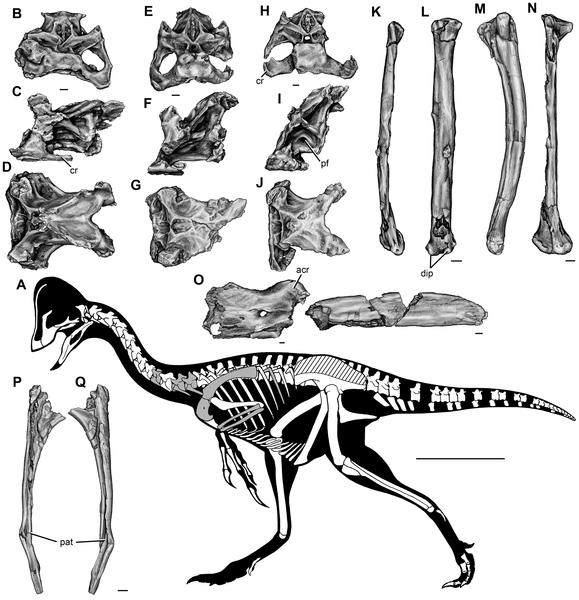

Researchers describe Anzu wyliei—also called the chicken from hell—an oviraptorosaurian looker at 3.5 meters long, 1.5m tall, with a body mass of about 200-300 kg, from the Hell Creek Formation in the Dakotas. Three well-preserved skeletons also indicate the dinosaur had a long neck and a short, thick tail.

In addition, the shape of the jaw places the dinosaur within the caenagnathid group, with its closest relative being the smaller, geologically older species Caenagnathus collinsi. The jaw shape and beak also reveal that Anzu was capable of feeding on a variety of food items, including vegetation, small animals, and possibly eggs. Ever wonder how they reconstruct a skull from broken pieces, illuminating the domed shape of the dinosaur’s head? Check out Figure 2 for a nice illustration.

Stick insects

Some insects are amazing at resembling leaves or branches to avoid predation. But when and where did this adaptation originate? Scientists saw few clues in the fossil record. But in PLoS ONE today, international researchers report on three specimens, one female and two males, belonging to a new fossil stick insect referred to as Cretophasmomima melanogramma, found in Inner Mongolia at a site dating from approximately 126 million years ago. The species possessed adaptive features that resembled a gingko plant recovered from the same location. This is the earliest documentation of this kind of mimicry.

The authors believe the insect used this plant as a model for concealment, as small insect-eating birds and mammals arrived on the scene (bonus points if you can find the Figure showing an artist’s interpretation of a stick insect meeting its fate on a gingko plant). The new fossils also suggest that leaf mimicry predated the appearance of twig and bark mimicry in these types of insects.

Bighorn sheep poop

Scientists are learning a lot from fossilized dung discovered on Tiburón Island, the largest island in the Gulf of California. The team, led by UC Riverside’s Benjamin Wilder, compared the pellet-shaped poop to fecal pellets of other large mammals and extracted DNA to sequence and determine the origin. The genetic analysis confirmed that the dung belonged to bighorn sheep, similar to those found in southern Arizona and California, but different from the current, introduced Tiburón population of bighorn sheep.

The scientists also performed carbon dating on the poop, suggesting that it originated about 1470-1630 years ago. They suggest that native desert bighorn sheep may have previously colonized the island when lower sea levels connected Tiburón to the mainland, most likely during the Pleistocene. They were likely eliminated within in the last 1500 years, probably due to inherent dynamics of isolated populations, prolonged drought, or human overkill.

“This finding raises a host of fascinating questions,” says Wilder, “Are bighorn sheep on Tiburón Island a restoration or a biological invasion? This extended biological baseline confirms that the Tiburón bighorn sheep went extinct before. Given the cultural and conservation significance of the unintentionally rewilded population, actions can be taken to avoid the same fate.”

Oh, we almost forgot to point you to the poop.

Image: doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0092022.g005