Science News

Kangaroo Tails

July 10, 2014

by Dannie Holzer

Imagine having an extra leg for when you get tired. One that could push you forward while the others took a break. Helping you move and eat at the same time. These are some of the advantages red kangaroos, the largest species in Australia, find in having a tail.

While in their lowered grazing stance, rather than using their feet, red kangaroos use their tail and forelimbs to lift themselves off the ground as they chew their way through grasslands—comparable to having two feet on a skateboard and having a third limb with which to push forward. But what’s even more impressive is the tail’s individual power as its own limb and not just its use as a crutch for walking.

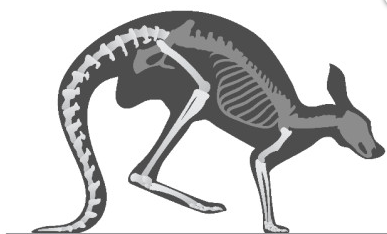

“Their tails have more than 20 vertebrae, taking on the role of our foot, calf, and thigh bones,” says Maxwell Donelan of Simon Fraser University. Donelan and his colleagues wanted to find the driving force behind what seems to be quite the evolutionary “leg up.”

In order to get an idea of a kangaroo’s true tail strength while walking pentapedally, researchers measured the force of its push on the ground by having the marsupial walk through a tunnel over a weight-sensored surface. The findings made them jump! Not only does a red kangaroo use its tail to help walk and balance, but also to conserve important energy.

The tail’s anatomy boasts large muscles (which cover all those vertebrae) similar in power to those used by the human leg while walking. These strong muscles give the tail more propulsive force than the fore and hind limbs combined! One advantage is that this already special feature “generates almost exclusively positive mechanical power,” according to the study, published last week in Biology Letters. This means that the kangaroo conserves its baseline energy independent of the tail force exerted.

And this is not only good for the kangaroo—for one thing, their small arms are better for balance mid-hop—but long term, it’s also great for the scientists (locomotive and otherwise), because it allows further insight on the mysterious evolutionary origins of the tail, whose direct purpose has long eluded scientists.

Dannie Holzer works in guest experience and as a production assistant at the California Academy of Sciences. In her spare time, she ’s a filmmaker.

Image: Heather More, Simon Fraser University