Science News

Music and the Brain

February 20, 2010

Music can help the brain with language.

At an AAAS Meeting press conference today, three neuroscientists spoke about the effect of music on language: specifically, the effect of music on listening, the effect of music on speaking and the effect of music on grammar.

Dr. Nina Krauss’s press release said it all, “Think twice about cutting music in school,†especially in the face of looming budget cuts. Her research focuses on how musicians, or even people with some musical experience, have “selective enhancement†for everyday listening. Experiments in her lab have proven that with musical training comes an ability to better discern and isolate sounds. And this can allow students with musical experience to pay more attention in noisy classrooms, she argues.

Dr. Gottfried Schlaug explained his work with patients who have suffered a stroke that has severely impaired the left side of the brain, negatively affecting their speech. Many cannot speak or formulate sentences because a lesion disturbs the connection between the auditory and motor parts of the brain. But singing can help this. A patient who could not say happy birthday could sing it. And these patients can be trained with musical therapy to first sing something like “I am thirsty†and then state it in a normal talking voice. The singing does not have to be professional; Schlaug and his team purposefully keep it simple so they can “teach caregivers how to do this at home.â€

Finally, Dr. Aniruddh Patel spoke about the similarities of musical compositions and grammatical compositions. He played a few melodies that contained errors that, even without musical training, could be detected. He explained that the brain can similarly sort out grammatical errors.

After these three presentations, a reporter asked which came first, music or speech? Dr. Patel noted that Darwin argued that singing came first, but it’s still up for debate. He followed up by saying that whichever came first, scientists can potentially use both music and speech to interact and help people.

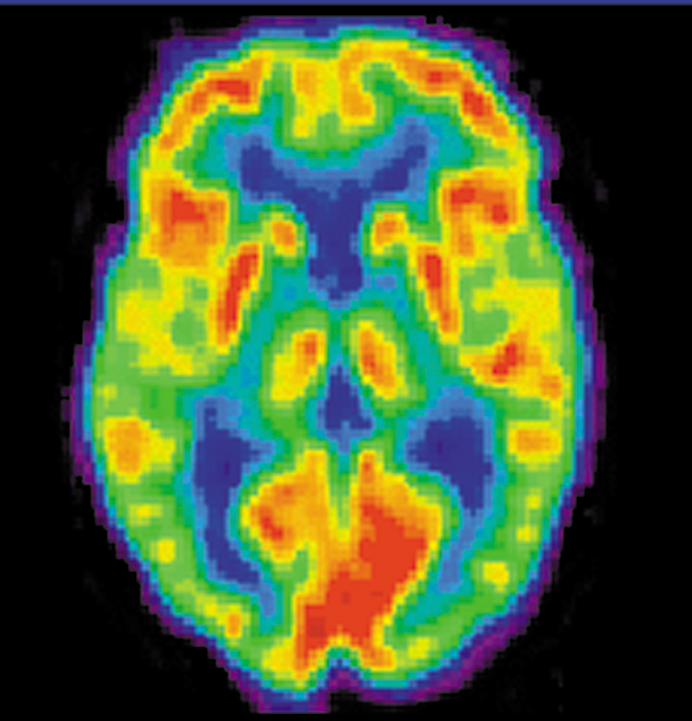

Image from NIH