Science News

No Drought in the Galaxy

March 11, 2014

by Elise Ricard

While California struggles with severe drought, announcements over the past few months have identified an abundance of water in a variety of places beyond our wet home world.

In December 2013, two teams examining Hubble data announced faint signatures of water on not one but five different exoplanets orbiting nearby stars. The observations were made in a range of low-energy wavelengths where a water signature, if present, would appear. The method is limited, however, to those rare planets spotted transiting their stars from our perspective on Earth.

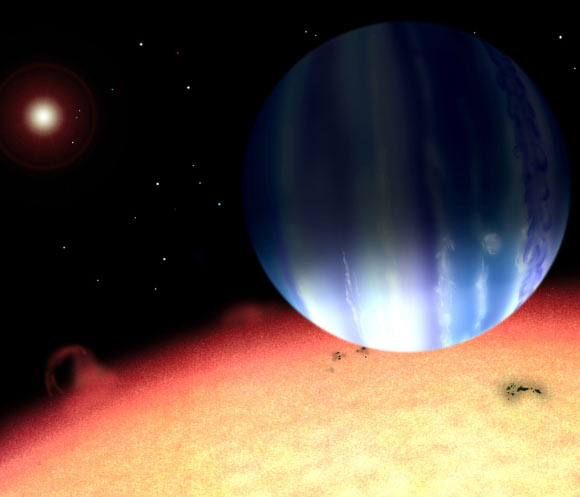

More recently, in February, water vapor was detected in the atmosphere of another giant world, tau Boötis b. This planet is much closer to Earth than those examined by Hubble, merely 50 light years away and implemented a different method. “We now are applying our effective new infrared technique to several other non-transiting planets orbiting stars near the Sun,” said Chad Bender, a research associate in the Penn State Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics. “These planets are much closer to us than the nearest transiting planets.” For now, this method can be used only on hot gas planets that are large and orbit close to a bright host star.

These planets are no Earths—they are “hot Jupiters,” many times more massive than our own gas giant and lacking a solid surface. While we’ve known for some time that other planets have the potential to harbor water, detecting it on these massive worlds serves more to enhance our understanding of their development rather than to detect signs of potential habitability for life.

In the future, new techniques and more-powerful future telescopes such as the James Webb Space Telescope may be able to examine the atmospheres of planets that are much cooler and more distant from their host stars, where liquid water—and the possibility for life—is more likely to exist.

Bringing the search closer to home, within our neighborhood the dwarf planet Ceres surprised scientists with plumes of water spewing from its surface. Similar events have been observed on at least two moons, Europa around Jupiter and Enceladus orbiting Saturn. Both are thought to harbor oceans underneath their surfaces that supply the watery vents, and Ceres may follow the model. The en-route Dawn mission should get a closer look.

Additional missions to explore watery worlds in our own solar system are being proposed as well.

Europa is thought to have a particularly expansive ocean of liquid water under its icy surface, and is an exceptionally enticing place to explore for the possibility of life. An orbiting spacecraft that could investigate the recently discovered plumes of ice that shoot up from the surface would make for a much easier (and cheaper) mission than landing on the Moon itself. Although NASA is considering a Europa-specific mission, the European Space Agency has already announced plans for the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (nicknamed “JUICE”), scheduled to launch in 2022.

Elise Ricard is a Senior Presenter and program contributor at the Morrison Planetarium. She also holds a master’s degree in museum education.

Image: tau Bootis b, David Aguilar/Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics