Science News

Rosetta Identifies Sinkholes on 67P

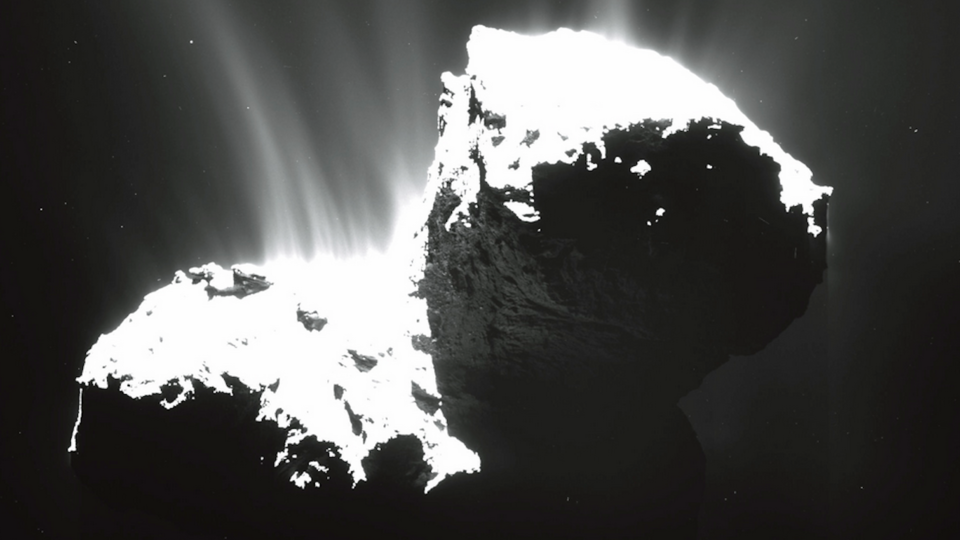

The jets spewing from comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko may be caused by sinkholes across the comet’s surface, which could provide a glimpse at the chaotic interior of the comet, according to an article describing the pits as published this week in Nature.

Since its historic arrival in the comet’s orbit last August, the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission has been mapping the surface of 67P with a dual camera system called the Optical Spectroscopic and Infrared Remote Imaging System (OSIRIS). During the process, scientists identified eighteen nearly circular pits, up to 650 feet across, on 67P’s illuminated northern hemisphere. Two distinct types of pits are noted: deep ones with steep sides and jets of gas and dust streaming from the sides, and shallower pits that more closely resemble those seen on other comets. “These strange, circular pits are just as deep as they are wide. Rosetta can peer right into them,” says Dennis Bodewits of University of Maryland.

“These can’t be impact craters,” explains Paul Weissman of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, “because there are too many big ones.” Impact craters would leave a predictable size distribution. Instead, they appear to be sinkholes responsible for some of the comet’s dust jets, which provide some insight into the interior of 67P and how the comet has changed over time.

Here on Earth, sinkholes are relatively common and occur when subsurface erosion removes a large amount of material beneath the surface, creating a ceilinged cavern that eventually collapses under its own weight.

Based on Rosetta observations, the team proposed a model for the formation of sinkholes on 67P. The team inferred that the interior of the nucleus is approximately 75–80 percent empty space, with numerous icy, cavern-like pockets. As ices under the surface sublimate, voids are created by their loss and depressions form as dust and other material collects in the basin. Eventually the ceilings of these voids collapse under their own weight to create large pits. The collapse exposes previously hidden, subsurface ices to the Sun’s heat for the first time, triggering even more sublimation of these ices and producing outbursts of gas and dust. Deeper pits are thought to be relatively new, while the shallower ones are most likely older sinkholes with more thoroughly eroded sidewalls and bottoms that have been filled in by dust and ice chunks.

The material ejected and sublimated from 67P has been a source of numerous of surprises in the last month, including observed emissions on the night-side of the comet and further insight into the processes that create the comet’s coma. Rosetta team members expect more interesting finds as 67P gets more active as it approaches to perihelion, its closest point to the Sun, next month. Last week, Rosetta was also granted a nine-month mission extension, into September 2016.

Image: MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/IDA