Science News

Space Friday: Celestial War and Peace, Titan, TNOs

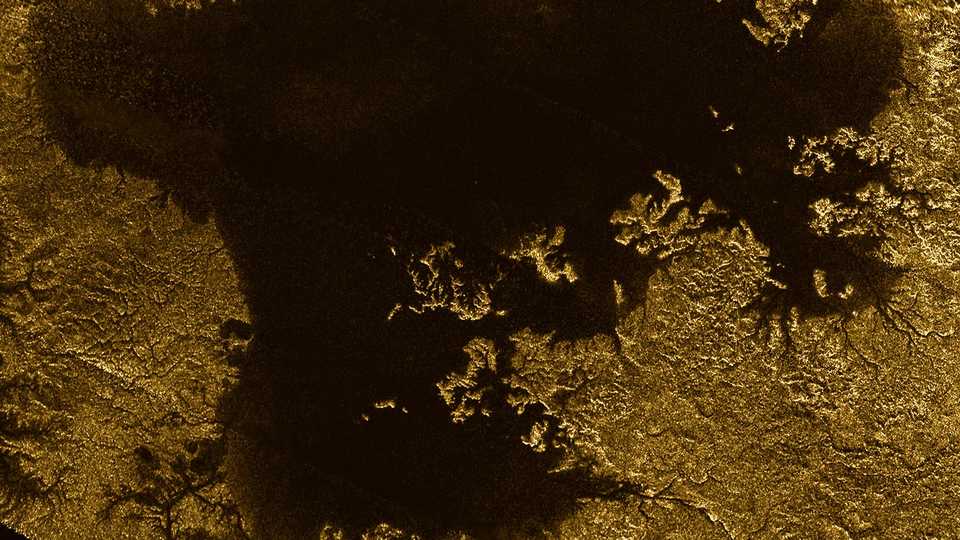

NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASI

How the Heavens Have Influenced War and Peace

A recent article in the American Geophysical Union's journal Space Weather, is getting a lot of attention, telling how activity on the surface of the Sun caused a scare in 1967. The effects of a solar flare disrupted radar systems designed to provide early warning to the U.S. military of a Soviet missile attack and, thinking the interference was a deliberate attempt to jam its surveillance network, the Air Force put its aircraft on alert, ready to counterattack. At the proverbial last minute, space weather experts explained the effects of solar storms to military commanders, averting a disaster and pointing out the benefits of solar monitoring to national security. Whew!

How many other close calls have there been? History reveals many instances where simple visual observations—and in more recent times, technological detections—have affected (or nearly affected) the course of war or peace. The Greek historian Herodotus wrote that in 585 BC, a total solar eclipse was seen from ancient Turkey, interrupting a five-year-long battle between the warring Lydians and Medes, who were so terrified that they agreed to peace.

In 413 BC, as chronicled by another Greek historian, Thucydides, Athenian forces fighting in the Second Peloponnesian War were in the process of withdrawing from Sicily after a series of setbacks. They were preparing to set sail from the port of Syracuse—which was controlled by their enemies, the Spartans—when a total lunar eclipse occurred, turning the Moon a frightening, blood-red color. This alarming spectacle prompted Athenian commanders to seek council from their priests, who told them to delay their departure for a month. This turned out not to be the best advice. The delay gave the defenders of Syracuse time to mount a fresh assault, delivering a devastating defeat to the Athenians.

In modern times, even though eclipses are much better understood than they were in antiquity, misidentification of celestial objects is common and has at least had the potential to lead to disaster. In 1993, the U.S. Department of Defense declassified 17 years of data, revealing that 136 explosions occurred in the atmosphere since 1975, each releasing energy in the kiloton range, or a thousand tons of TNT (for comparison, the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima had a yield of 15 kilotons). The report revealed the hazards of incoming meteoroids that explode high above the ground as airbursts. One such event highlighted in the report occurred above the western Pacific Ocean on October 1, 1990, during the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. The explosion released about two kilotons of energy, and Simon Worden, who was instrumental in getting the airburst data declassified, notes that had it occurred closer to the Middle East instead of over the Pacific, "it could have been a sticky situation. We could tell it was natural, but they could not," and might have been interpreted by jittery troops on the ground as a major attack. (The effects of such an airburst are explored in Morrison Planetarium's award-winning show, "Incoming!," by way of a visualization of the 2013 explosion over Chelyabinsk, Russia).

More recently, in 2013, Indian soldiers stationed along the disputed Himalayan border between India and China reported 329 sightings of what they thought were Chinese drones over a six month period. Of those sightings, 155 were described as incursions across the border. After consulting with astronomers from the Indian Institute of Astrophysics, they found out that what they'd been observing were misidentified—they were actually the planets Jupiter and Venus.

There are many more examples, but they all point to the importance of understanding the Universe around us as much as possible and being able to separate natural events from human-caused ones—it could help prevent a war. –Bing Quock

Deep Flowing Canyons on Titan

“Earth is warm and rocky, with rivers of water, while Titan is cold and icy, with rivers of methane. And yet it’s remarkable that we find such similar features on both worlds,” says Alex Hayes, co-author of a new study on Saturn’s largest moon.

Hayes and his colleagues used NASA’s Cassini spacecraft to confirm the existence of very deep, very steep canyons with actively flowing methane on the moon’s surface. This makes Titan the only planetary body in our solar system, other than Earth, to have a surface actively eroding on a large scale, says Rosaly Lopes of NASA, who is not connected to the study. “We have seen some canyons elsewhere, such as Valles Marineris on Mars. However, on Titan, this study shows evidence that some canyons are still filled with liquid and presumably in the process of carving canyons.”

Cassini’s radar observations of Titan’s north pole depict cavernous gorges a little less than a kilometer (less than half a mile) wide with walls up to 570 meters (1870 feet) tall. The eight canyons branch off from Vid Flumina, a more than 400-kilometer (249-mile) long river flowing into Titan’s second-largest sea, Ligeia Mare.

The study’s authors draw comparisons between Titan’s canyons and Arizona and Utah’s Lake Powell and the Nile River gorge. All feature canyons and valleys etched by erosion from flowing liquid. The deep cuts in Titan’s landscape indicate the process that created them occurred over multiple extended periods, though the age of that process remains uncertain. They could have been created by uplift of the terrain or changes in sea level, or both, according to the study’s authors.

Studying the geologic processes on Titan can help researchers tease apart its origins and conditions on early Earth. Titan allows scientists to see how these processes change under varying conditions, like changes in temperature, according to Lopes. “On Earth we can’t vary the conditions like surface temperature and atmospheric density to see how geologic processes would behave,” she explains. But by turning to Titan, scientists can see how familiar processes could change when those conditions are altered.

“Although the term is overused, Titan is really a ‘natural laboratory’ for understanding geological processes,” Lopes says. –Molly Michelson

Backwards Orbiting Planetoid

Scientist using the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System 1 Survey (Pan-STARRS 1) on Haleakala, Maui have discovered an interesting small,124 mile (200 kilometer) diameter, planetoid in the very outer solar system. The trans-Neptunian object (TNO) is called Niku, a Chinese word for "rebellious" and it earns it name–it orbits the opposite direction of almost all other solar system objects. Not only that, the plane of its orbit is tilted 110 degrees off the plane of the rest of the solar system.

So what’s going on here?

“Angular momentum forces everything to have that one spin direction all the same way,” says Michele Bannister of Queens University. “It’s the same thing with a spinning top, every particle is spinning the same direction.” Unless of course, it has been been knocked off course by a physical or gravitational encounter with something else, causing the strange spin or orbit. So far, however, various possible explanation for Niku’s orbit, including the hypothesized Planet Nine, an unseen dwarf star called Nemesis, or an unknown dwarf planet in the Kuiper Belt are all "problematic" according the publication of the discovery (which can be viewed here).

Discoveries like Niku “suggests that there’s more going on in the outer solar system than we’re fully aware of,” says Matthew Holman at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. –Elise Ricard