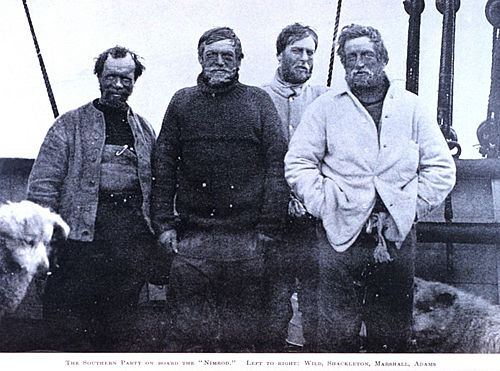

Back in this blog's first post, I introduced Aurora Australis, the first book ever published in Antarctica. I talked briefly about its significance to my project and promised more information on the edition's creation. Here it is, as a prelude to tomorrow's visit to Shackleton's Hut at Cape Royds where this book was born.  Aurora Australis was created during the British Antarctic Expedition of 1907-09, also known as the Nimrod Expedition. The voyage was led by Ernest Shackleton with the aim of making the first successful journey to the South Pole. He made it to within a hundred miles of his goal, setting a new record for southernmost travel. The expedition's other accomplishments included the discovery of the location of the South Magnetic Pole, first traverse of the Trans-Antarctic mountain range, first travel on the South Polar Plateau, discovery of the Beardmore Glacier, and the first ascent of Mount Erebus. These feats were achieved in teams. The Southern Party shown above made the attempt on the Pole. Left to right: Frank Wild, Ernest Shackleton, Eric Marshall, and Jameson Boyd Adams.

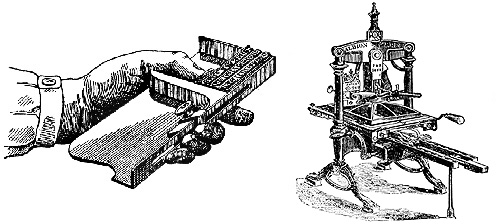

Aurora Australis was created during the British Antarctic Expedition of 1907-09, also known as the Nimrod Expedition. The voyage was led by Ernest Shackleton with the aim of making the first successful journey to the South Pole. He made it to within a hundred miles of his goal, setting a new record for southernmost travel. The expedition's other accomplishments included the discovery of the location of the South Magnetic Pole, first traverse of the Trans-Antarctic mountain range, first travel on the South Polar Plateau, discovery of the Beardmore Glacier, and the first ascent of Mount Erebus. These feats were achieved in teams. The Southern Party shown above made the attempt on the Pole. Left to right: Frank Wild, Ernest Shackleton, Eric Marshall, and Jameson Boyd Adams.  Before departing England, Shackleton conceived the idea of printing a book as an activity to occupy his men during the dark, cold winter months in their Ross Island hut. They hauled what Shackleton describes as a "complete printing outfit" to Antarctica including a hand-press similar to the one shown here for printing movable metal type, and an etching press to print the illustrations. The composing stick on the left is used for setting type prior to positioning it in the press.

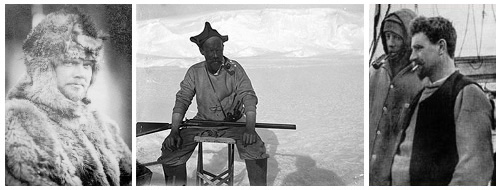

Before departing England, Shackleton conceived the idea of printing a book as an activity to occupy his men during the dark, cold winter months in their Ross Island hut. They hauled what Shackleton describes as a "complete printing outfit" to Antarctica including a hand-press similar to the one shown here for printing movable metal type, and an etching press to print the illustrations. The composing stick on the left is used for setting type prior to positioning it in the press.  Aurora Australis is an anthology of the party's personal writings, poetry, and narratives both fiction and non-fiction. Shackleton edited the 120-page book, wrote its two prefaces, and contributed an ode to Mount Erebus under the pseudonym "NEMO." George Marston (left) was the official expedition artist. He created and printed Aurora Australis's title pages and twelve illustrations by algraphy -- printing from aluminium plates. Frank Wild (center) and Ernest Joyce (right, foreground) printed the text with the benefit of only 3 weeks' training in lieu of the usual seven years of print shop apprenticeship.

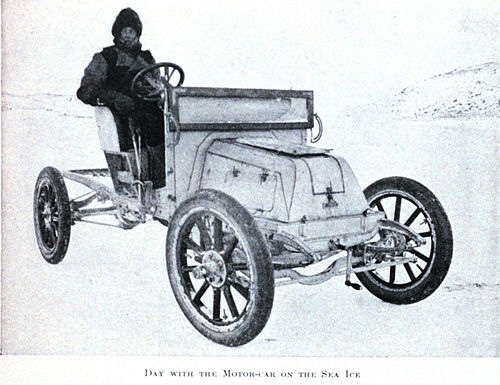

Aurora Australis is an anthology of the party's personal writings, poetry, and narratives both fiction and non-fiction. Shackleton edited the 120-page book, wrote its two prefaces, and contributed an ode to Mount Erebus under the pseudonym "NEMO." George Marston (left) was the official expedition artist. He created and printed Aurora Australis's title pages and twelve illustrations by algraphy -- printing from aluminium plates. Frank Wild (center) and Ernest Joyce (right, foreground) printed the text with the benefit of only 3 weeks' training in lieu of the usual seven years of print shop apprenticeship.  The book was bound by Bernard Day, the electrician and mechanic, seen here taking the first motor car in Antarctica for a spin on the sea ice. (The car, built and donated by Arrol-Johnston company of Paisley, Scotland, ultimately failed to perform in the cold and the snow.)

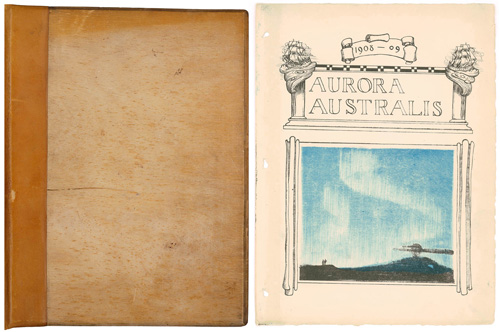

The book was bound by Bernard Day, the electrician and mechanic, seen here taking the first motor car in Antarctica for a spin on the sea ice. (The car, built and donated by Arrol-Johnston company of Paisley, Scotland, ultimately failed to perform in the cold and the snow.)  Day fashioned wooden covers from provisions cases, made spines from harness leather, and bound the perforated pages with green silk cord. Only about 25 of approximately 90 printed copies were bound. These are often referred to by the writing on the packing crate boards -- the Huntington has the 'Blueberries' copy for example, while the National Library of New Zealand has the ‘Julienne Soup’ and ‘Beans’ copies.

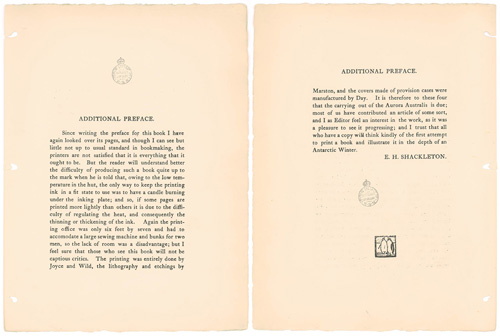

Day fashioned wooden covers from provisions cases, made spines from harness leather, and bound the perforated pages with green silk cord. Only about 25 of approximately 90 printed copies were bound. These are often referred to by the writing on the packing crate boards -- the Huntington has the 'Blueberries' copy for example, while the National Library of New Zealand has the ‘Julienne Soup’ and ‘Beans’ copies.  In the book's prefaces, Shackleton describes the adverse conditions under which the book was produced. James Murray, the expedition's biologist, elaborates further with this fantastic account in his book Antarctic Days: "The reader, contemplating the finished work, would have no glimmering of suspicion of the immense difficulties under which the work had to be produced. It was winter, and dark, and cold. The work had to be done, in the intervals of more serious occupations, in a small room occupied by fifteen men, all of them following their own avocations, with whatever of noise, vibration and dirt might be incidental to them. The inevitable state of such a hut, after doing all possible for cleanliness, can be imagined. Fifteen men shut up together, say during a blizzard which lasts a week. Nobody goes out unless on business; every one who goes out brings in snow on his feet and clothes. Seal-blubber is burned, mixed with coal, for economy. The blubber melts and runs out on the floor; the ordinary unsweepable soil of the place is a rich compost of all filth, cemented with blubber, more nearly resembling the soil of a whaling-station than anything else I know. Dust from the stove fills the air and settles on the paper as it is being printed. If anything falls on the floor it is done for; if somebody jogs the compositor’s elbow as he is setting up matter, and upsets the type into the mire, I can only leave the reader to imagine the result. The temperature varies; it is too cold to keep the printer’s ink fluid; it gets sticky, and freezes. To cope with this a candle was set burning underneath the plate on which the ink was. This was all right, but it made the ink too fluid, and the temperature had to be regulated by moving the candle about. Once the printers were called away while the candle was burning, and nobody happened to notice it. When they returned they found that the plate had overheated and had melted the inking roller of gelatinous substance. I believe it was the only one on the Continent and had to be re-cast somehow. So much for the ordinary printing. The lithography was still worse. All the evils enumerated above persecuted the lithographer, and he had others all to himself. The more delicate part of his work could not be done when the hut was in full activity, with vibration, noise and settling smuts, so Marston used to do most of his printing in the early hours of the morning, when the hut was as nearly quiet and free from vibration as it ever became, and there was a minimum of dust (at least in suspension in the air). I had the opportunity of observing his tribulations, as, for similar reasons, I found the early hours best for biological study. At these hours the number of loafers round the stove (drinking tea) might be reduced to three or four, or even fewer. I do not pretend to know the nature of the special difficulties that the climate introduced into lithography, but I know this, that I’ve frequently seen Marston do everything right—clean, ink, and press—but for some obscure reason the prints did not come right. And I’ve seen him during a whole night pull off half a dozen wrong ones for one good print, and he did not use so much language over it as might have been expected."

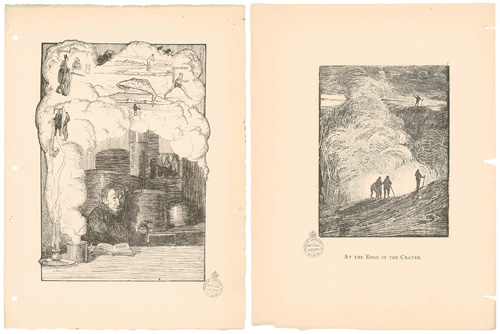

In the book's prefaces, Shackleton describes the adverse conditions under which the book was produced. James Murray, the expedition's biologist, elaborates further with this fantastic account in his book Antarctic Days: "The reader, contemplating the finished work, would have no glimmering of suspicion of the immense difficulties under which the work had to be produced. It was winter, and dark, and cold. The work had to be done, in the intervals of more serious occupations, in a small room occupied by fifteen men, all of them following their own avocations, with whatever of noise, vibration and dirt might be incidental to them. The inevitable state of such a hut, after doing all possible for cleanliness, can be imagined. Fifteen men shut up together, say during a blizzard which lasts a week. Nobody goes out unless on business; every one who goes out brings in snow on his feet and clothes. Seal-blubber is burned, mixed with coal, for economy. The blubber melts and runs out on the floor; the ordinary unsweepable soil of the place is a rich compost of all filth, cemented with blubber, more nearly resembling the soil of a whaling-station than anything else I know. Dust from the stove fills the air and settles on the paper as it is being printed. If anything falls on the floor it is done for; if somebody jogs the compositor’s elbow as he is setting up matter, and upsets the type into the mire, I can only leave the reader to imagine the result. The temperature varies; it is too cold to keep the printer’s ink fluid; it gets sticky, and freezes. To cope with this a candle was set burning underneath the plate on which the ink was. This was all right, but it made the ink too fluid, and the temperature had to be regulated by moving the candle about. Once the printers were called away while the candle was burning, and nobody happened to notice it. When they returned they found that the plate had overheated and had melted the inking roller of gelatinous substance. I believe it was the only one on the Continent and had to be re-cast somehow. So much for the ordinary printing. The lithography was still worse. All the evils enumerated above persecuted the lithographer, and he had others all to himself. The more delicate part of his work could not be done when the hut was in full activity, with vibration, noise and settling smuts, so Marston used to do most of his printing in the early hours of the morning, when the hut was as nearly quiet and free from vibration as it ever became, and there was a minimum of dust (at least in suspension in the air). I had the opportunity of observing his tribulations, as, for similar reasons, I found the early hours best for biological study. At these hours the number of loafers round the stove (drinking tea) might be reduced to three or four, or even fewer. I do not pretend to know the nature of the special difficulties that the climate introduced into lithography, but I know this, that I’ve frequently seen Marston do everything right—clean, ink, and press—but for some obscure reason the prints did not come right. And I’ve seen him during a whole night pull off half a dozen wrong ones for one good print, and he did not use so much language over it as might have been expected."  Last summer I had the opportunity to leaf through the Huntington Library's copy with Gloria Kondrup, director of Art Center's Archetype Press in Pasadena. We marveled over the materials and craftsmanship of the book, especially given Murray's description of the ordeal. Shown above are Marston's prints Night Watchman and At the Edge of the Crater.

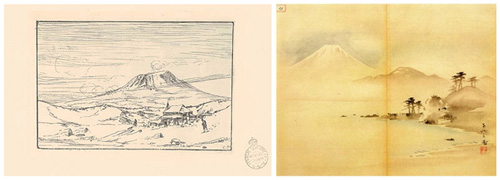

Last summer I had the opportunity to leaf through the Huntington Library's copy with Gloria Kondrup, director of Art Center's Archetype Press in Pasadena. We marveled over the materials and craftsmanship of the book, especially given Murray's description of the ordeal. Shown above are Marston's prints Night Watchman and At the Edge of the Crater.  We also perceived Japanese artist Hiroshige's profound influence on Marston's style. Side-by side comparisons of the two seem to bear this out. On the left, Marston's Under the Shadow of Erebus; on the right, Hiroshige's Mount Fuji Viewed from Inlet.

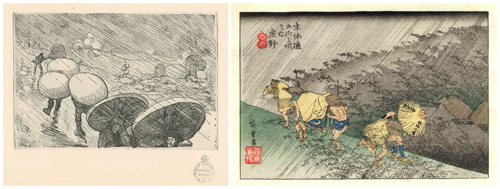

We also perceived Japanese artist Hiroshige's profound influence on Marston's style. Side-by side comparisons of the two seem to bear this out. On the left, Marston's Under the Shadow of Erebus; on the right, Hiroshige's Mount Fuji Viewed from Inlet.  On the left, Marston's Each Sheltered Under One of the Novel Umbrellas; on the right, Hiroshige's Shono from the 53 Stations of the Tokaido. Marston's reverence for the ukiyo-e master was shared by many European artists of the time, notably the French Impressionists such as Monet, and Van Gogh who copied two of Hiroshige's prints that he owned. Aurora Australis was not offered for sale to the general public; all the copies were privately distributed among friends and benefactors. The small edition size prevented wide readership until the first facsimile edition was published in 1986 -- minus the wooden boards. Today the entire book can be accessed online page by page at the State Library of New South Wales site.

On the left, Marston's Each Sheltered Under One of the Novel Umbrellas; on the right, Hiroshige's Shono from the 53 Stations of the Tokaido. Marston's reverence for the ukiyo-e master was shared by many European artists of the time, notably the French Impressionists such as Monet, and Van Gogh who copied two of Hiroshige's prints that he owned. Aurora Australis was not offered for sale to the general public; all the copies were privately distributed among friends and benefactors. The small edition size prevented wide readership until the first facsimile edition was published in 1986 -- minus the wooden boards. Today the entire book can be accessed online page by page at the State Library of New South Wales site.