Universe Update

Asteroid Masquerade

Why would you cut a giant hole in a Boeing 747SP, load it up with a 2.5-meter (100-inch) telescope, and fly it around the world at altitudes of about 12 kilometers (40,000 feet)? To blow the cover on masquerading asteroids, that’s why!

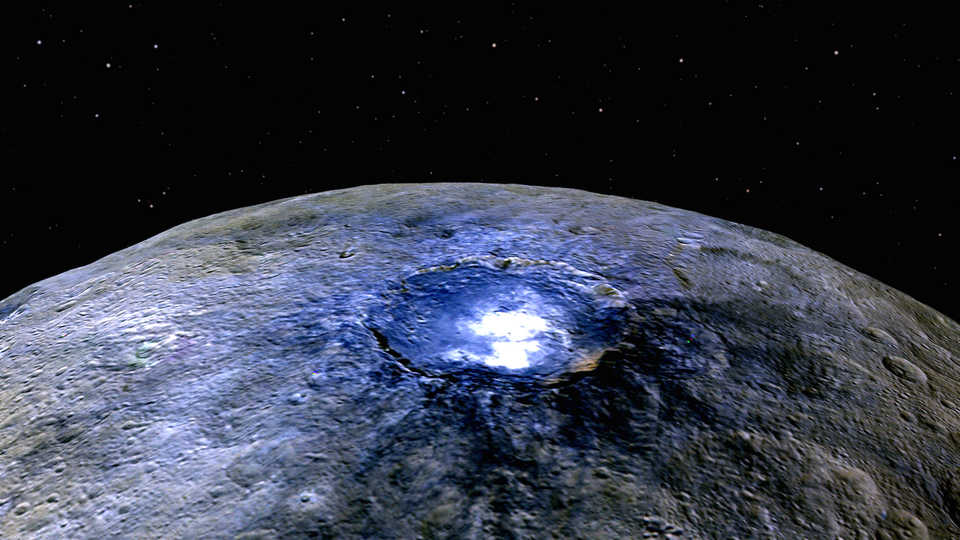

Well, there are actually plenty of reasons why NASA (in collaboration with German Aerospace Center DLR) operates the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), but observing asteroids is indeed one of them. And new research from SOFIA suggests that the largest of the asteroids (a.k.a. the lone inner Solar System dwarf planet), Ceres, is disguised under a veil of material from other asteroids!

“We find that the outer few microns of the surface is partially coated with dry particles,” according to Franck Marchis of the SETI Institute and co-author of the study. “But they don’t come from Ceres itself. They’re debris from asteroid impacts that probably occurred tens of millions of years ago.

“Ceres is still a wet asteroid as shown by the Dawn mission, but our work implies that the surfaces of asteroids do not fully reflect their interiors. If we want to find water or rare minerals in an asteroid, then we will have to dig—or at least study it in detail to assess its true composition. Contamination between asteroids is complicating our lives.”

For virtually all asteroids, we can only observe their surfaces (indeed, we see most of them as mere points of light in our telescopes). How does this complicate Marchis’s (presumably research) life? Because our surface view may conceal what’s really going on with the composition of these asteroids—beautiful or not, the observations are only skin deep.

SOFIA’s unique contribution comes in the form of observations in mid-infrared light—wavelengths of light that Earth’s atmosphere absorbs, preventing mid-infrared observations from the ground. That’s where cutting a hole in a 747 comes in! SOFIA flies above most of the obscuring moisture in the atmosphere, so the high-flying observatory can look for tell-tale signs of chemical compounds otherwise unseen in other wavelengths of light.

In this case, SOFIA identified a dry silicate called pyroxene on Ceres’s surface, which comes as a bit of a surprise, since Ceres is generally considered a “wet” asteroid (but really only compared to other, so-called “dry” asteroids). Where did this veneer of dry stuff come from? Well, we know of surfaces in the Solar System discolored by debris from other objects (just look at Saturn’s moon Iapetus and Pluto’s moon Charon), so it seems likely that debris from some of Ceres’s dry and rocky neighbors may have tinted the dwarf planet, too.

It required looking at Ceres in mid-infrared light to reveal these compositional differences, which suggests that similar observations can help us unmask other masquerading asteroids. More work for SOFIA! Or perhaps a future space-based mission.

Marchis posted on his blog about the discovery, so you can learn more about it from his postscript to the announcement. For some related work, you can also check out our video of Marchis describing his work on asteroid moons. Marchis also advised the Academy’s production team on our latest planetarium show, Incoming!, now showing at Morrison Planetarium.

Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA