Science News

Monday Bites: Coral Reefs

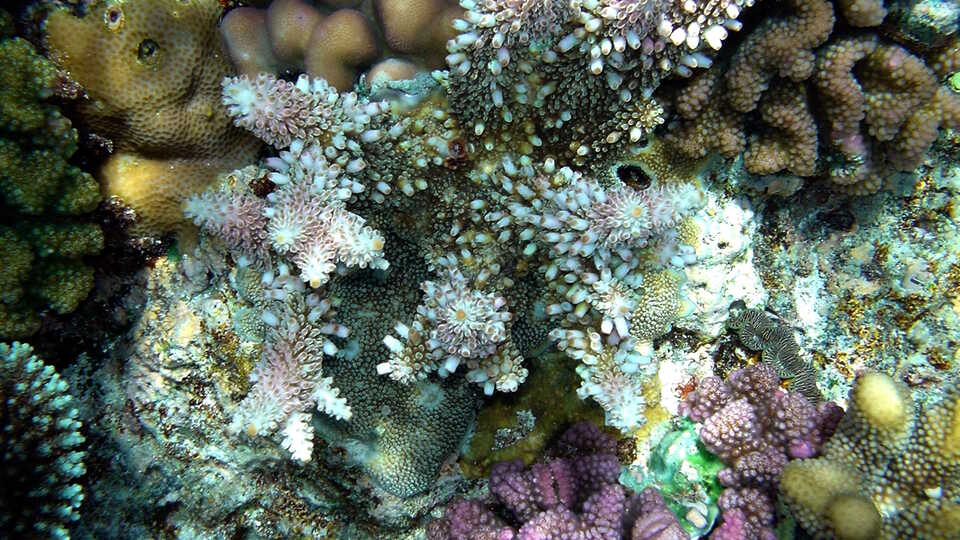

Coral reefs are being pummeled by many threats: warming oceans that cause coral bleaching, higher acidity that weakens the animals’ exoskeletons, overfishing, and dredging. But scientists are working hard to find solutions to these problems and protect these fragile and incredibly important ecosystems. Coral reefs are essential both to ocean life—they harbor 25 percent of marine species, but cover less than 1 percent of the world’s oceans—and human life. Economically, these reefs are worth tens of billions of dollars. Several recent studies look at the threats to these magnificent habitats and the potential solutions to these challenges.

Great Barrier Reef Bleaching

Last week, scientists announced the most severe bleaching event ever to hit the Great Barrier Reef, off the coast of Queensland, Australia. Bleaching occurs when warmer water causes coral to expel their zooxanthellae, tiny algae that live in the coral and provide the corals nutrients and energy. If the water warms for only a short period, the corals can generally recover and regain their zooxanthellae; but longer periods of warmth can cause the corals to die. In this case, aerial surveys, multiple research vessels, and island research stations reveal that warm summer temperatures (thanks in large part to the current El Niño) are causing bleaching and significant die-offs, too. “Scientists in the water are already reporting up to 50% mortality of bleached corals,” says Terry Hughes, convenor of the Australian National Coral Bleaching Taskforce. “But it’s still too early to tell just what the overall outcome will be… We’ll be conducting further aerial surveys this week in the central Great Barrier Reef to identify where it stops. Thankfully, the southern Reef has dodged a bullet due to cloudy weather that cooled the water temperatures down.” The taskforce is stepping up their monitoring efforts over the next few weeks.

Adapting to Warmer Waters

Some corals have naturally adapted, over time, to withstand warmer waters and thus not bleach, as we have reported here and here. So scientists Madeleine van Oppen and Ruth Gates proposed helping other corals adapt to warming with assisted evolution in a paper last year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. “Assisted evolution is the acceleration of naturally occurring evolutionary processes to enhance certain traits. Various AE approaches have been widely used for the improvement of commercial species, including crop species, wood trees and livestock,” van Oppen says.

“Observations indicate that under the right circumstances, acclimatization or adaptation can occur over relatively short time scales. If we could promote and enhance this natural adaptive ability across several coral species then this could help increase reef resilience in the face of current and future climate change,” says Gates. “This is important as the economic value of coral reefs through commercial and recreational fisheries, tourism, drug discovery, and coastal protection is immense.”

Stop Coral Dredging in the South China Sea

“Countries bordering the South China Sea need to realize that the value of the Spratly Islands as a spawning ground for the same fish that support the lives and livelihoods of their citizens—a source of larvae to replenish harvested fish populations throughout the region.” In a recent paper in PLoS Biology, John MacManus and his colleagues urge the international community to stop the dredging of the distant seven atolls known as the Spratly Islands. The dredging is increasing the land on the islands but damaging or destroying the surrounding coral reefs. The authors used remote sensing data from the Landsat 8 Operational Land Imager to quantify reef destruction and land creation from February 2014 to May 2015. Since the territory is disputed, the authors suggest the establishment of a multinational marine protected area, with the formation of the Antarctica Protected Areas as a positive example of an ecologically important region saddled with multiple territorial claims.

Protecting Corals from Ocean Acidification

“Ocean acidification is particularly troublesome for coral reefs because the entire structure of the ecosystems is built upon the calcium carbonate skeletal remains of dead coral,” says Stanford’s David Koweek. “Ocean acidification makes it difficult for corals to calcify and makes it easier to erode these skeletal remains, threatening the integrity of the entire reef.” So Koweek and his colleagues have come up with a method for reducing ocean acidification near coral reefs: blowing tiny bubbles. In a study published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, the team reports that their technique strips carbon dioxide (CO2) from the marine environments and transfers it to the atmosphere by bubbling air through seawater for a few hours in the early morning, when the waters are most acidic.

Koweek thinks bubble stripping could prove useful for protecting small sections of shallow coastline that are ecologically, culturally, or commercially important. Because the operations would be small, the benefits to the marine environments from lowering ocean acidity levels would greatly outweigh the relatively small amount of atmospheric CO2 generated by the bubbling process and by the compressors used to produce the bubbles. “If this idea takes off, you could imagine people running these compressors on solar power,” he says. “In the tropics, where there’s a lot of sunlight, you could charge your compressors with solar energy during the day and then bubble at night.”

Protect Parrotfish, Protect Corals

Can one family of fish protect coral reefs? In the Caribbean, parrotfish might help the resilience of coral reefs according to a study published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Parrotfish help keep seaweed under control and help corals recover, so several countries have banned catching the beaky fish. But with other countries continuing to fish this family, scientists wondered how effective further bans could be, so they developed a model to predict the future impact of different fishery regulations and climate change on harvest sustainability and reef health. The model showed that introducing size limits to an overfished ecosystem would both increase yield and reduce the impacts on corals. Compared with unregulated trap fishing, the implementation of limiting the harvest to 10% and enforcing a 30-centimeter (12-inch) body size could boost reef resilience—the probability that a reef would grow in 2030 despite climate-driven disturbances. Good for reefs and sustainable seafood? It’s a win-win!

Image: Brocken Inaglory/Wikipedia