Science News

Planets, Planets, Planets

January 12, 2012

by Ryan Wyatt

Reporting from day three of the American Astronomical Society meeting in Austin, Texas…

As you almost certainly already know, astronomers have found many, many planets in orbit around stars other than the Sun. My iPhone app tells me there are 725 such known extrasolar planets or “exoplanets.” With that many objects to study, and new ones being discovered like clockwork, astronomers have started to characterize different kinds of planets and planetary systems.

One nagging (well, intriguing) question is how many planets exist. Exoplanets certainly seem to be plentiful, but how plentiful, exactly? One of today’s announcements makes a bold claim: "Our Milky Way galaxy contains a minimum of 100 billion planets according to a detailed statistical study based on the detection of three extrasolar planets by an observational technique called microlensing. … [Our] galaxy contains a minimum of one planet for every star on average. This means that there is likely to be a minimum of 1,500 planets within just 50 light-years of Earth."

Well, okay, that’s exciting, and very possibly true, but note that phrase, “based on the detection of three extrasolar planets.” I like statistics as much as the next person, but a large gulf separates the numbers three and 100 billion. Looking at the abstract (brief summary) of the article online, I would draw attention to the uncertainty in the numbers they present—for example, they estimate that the percentage of stars with “super-Earths” (planets five to ten times as massive as Earth) effectively lies between 25% and 97%. That’s quite a range!

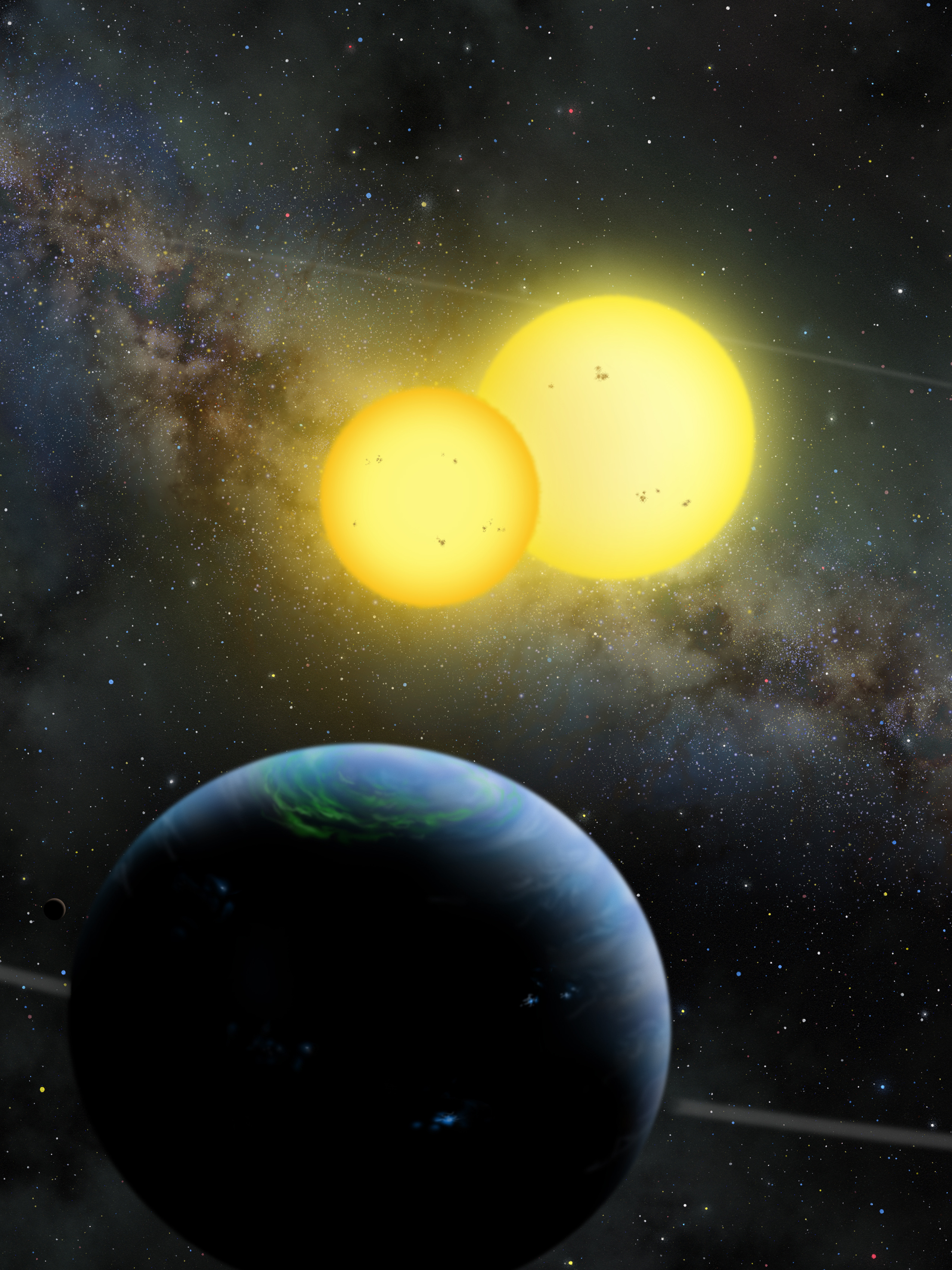

William Welsh, of San Diego State University, announced two new planets discovered by the Kepler mission, creatively named Kepler-34b and Kepler-35b. He described the planets as “fluffy Saturns,” far bigger than Earth and too close to their parent stars for liquid water to exist on their surfaces (well, if they have surfaces, cf. that “fluffy” descriptor). What makes them special? They both revolve around binary stars: in other words, each planet orbits two stars, which in turn revolve around one another.

Previously, the planet Kepler-16b had made news as “the real Tatooine” (at least that’s how we described it on Science Today back in September), making reference to the Skywalker clan’s home planet in Star Wars. So now we know of three such examples—a “new class of planetary systems,” in Welsh’s words—and astronomers expect to find many more.

Another Kepler announcement came from John Johnson at Caltech. Working with publicly available data, his team discovered an unusual little collection of planets: the smallest planets yet detected (all smaller than Earth, with the smallest about the size of Mars, the most compact system of planets ever discovered, and the least massive star known to harbor a planet (a red dwarf). A lot of firsts! Because the discoveries don’t come from the official Kepler team, they are designated KOI 961.03, KOI 961.02, and KOI 961.01 (where “KOI” stands for “Kepler Object of Interest”).

BTW, the parent star KOI 961 is only 70% larger than Jupiter, and indeed, the planets orbit the star in distances similar to the Jupiter system… So personally, I like the diagram that compares the system to Jupiter and its moons.

Johnson also fired off one of the better quips at the meeting: “transiting planets are like cockroaches—if you see one, you know there are others [you’re not seeing].” The reason? A planet only appears to transit its parent star from a particular vantage point, which means that for every one we observe to transit, there are presumably many more that we don’t see because the geometry isn’t quite right.

Also, on April 2nd, Johnson will speak at the Academy’s Morrison Planetarium as part of our Benjamin Dean Lecture Series. His talk, “The Quest for Habitable Planets Orbiting Red Dwarfs,” will give attendees an opportunity to learn more about KOI 961—as well as more exciting results to come!

Ryan Wyatt is the director of the Morrison Planetarium and Science Visualization at the California Academy of Sciences.