Science News

Salps: Ocean Vacuums

Smaller is better, at least where salps’ food is concerned.

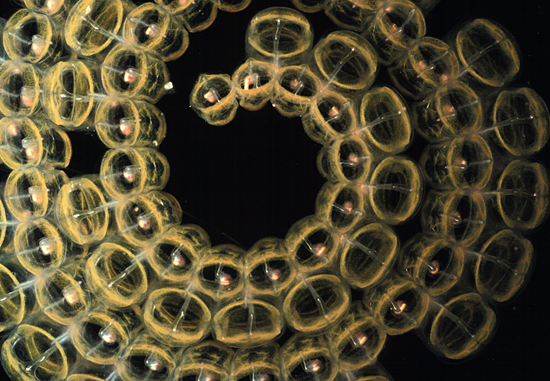

Salps are a type of tunicate or sea squirt, small gelatinous creatures that live in the oceans and are chordates, which makes them more closely related to us than they are to the jellyfish they resemble. They can exist either singly or in chains that may contain a hundred or more of the five-inch animals (National Geographic has a great video on YouTube of a long salp chain).

Salps are known to be efficient eaters and in fact, as this older article in Discover points out,

Moving and eating are the same thing for them. As water flows into one open end of the barrel, the barrel contracts, shooting the water out the back and pushing the salp forward. On its way, though, the water passes through an internal net of mucus, sort of like a sleeve lining, that strains out particles as small as bacteria.

(These creatures are so efficient, the article continues, numerous parasites love salps.)

Recent research published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), illuminates how impressive and important these little ocean vacuums are.

According to LiveScience,

…The new results show these animals can consume particles that span a huge size range, or about four orders of magnitude, from a fraction of a micrometer to a few millimeters. If sized up that range would be like eating everything from a mouse to a horse, [co-author Larry] Madin said.

And in fact, they prefer the smaller particles. Again from LiveScience:

In the laboratory at WHOI, [lead author Kelly] Sutherland and her colleagues offered salps food particles of three sizes: smaller, around the same size as, and larger than the mesh openings.

“We found that more small particles were captured than expected,” said Sutherland, now a post-doctoral researcher at Caltech. “When exposed to ocean-like particle concentrations, 80 percent of the particles that were captured were the smallest particles offered in the experiment.”

According to Madin, “Their ability to filter the smallest particles may allow them to survive where other grazers can't.”

Perhaps most significantly, the result enhances the importance of the salps’ role in carbon cycling. As they eat small and large particles, “they consume the entire ‘microbial loop’ and pack it into large, dense fecal pellets,” Madin says.

The larger and denser the carbon-containing pellets, the sooner they sink to the ocean bottom. “This removes carbon from the surface waters,” says Sutherland, “and brings it to a depth where you won't see it again for years to centuries.”

But wait, there’s more. Co-author Roman Stocker of MIT says that the more carbon that sinks to the bottom, the more space there is for the upper ocean to accumulate carbon, hence limiting the amount that rises into the atmosphere as CO2.

Thanks, salps!

Image Kelly Sutherland and Larry Madin, WHOI