Science News

US Methane Emissions

December 2, 2013

by Molly Michelson

Carbon dioxide isn’t the only emission contributing to climate change. Methane emissions also play a significant role in trapping atmospheric heat and raising global temperatures.

Although methane emissions result from several natural causes, roughly 60 percent of the global output can be traced back to human activities. Primary culprits include the extraction and refining of oil and natural gas, coal mining, landfills, cattle farming, and manure management.

But the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimated that methane emissions in the United States were dropping significantly, “largely citing sharp decreases in discharges from gas production and transmission, landfills and coal mines,” according to the New York Times.

But Anna Michalak, of the Carnegie Institution for Science and Stanford's Department of Environmental Earth System Science, says the EPA’s estimates are wrong—methane emissions in the United States remain high.

The EPA came to its conclusions by estimating the amount of methane produced per cow or per unit of fossil fuel produced and then extrapolating to calculate total emissions. “We call this a bottom-up approach,” says Michalak. “It is essentially a bookkeeping approach, and the uncertainties of the individual line items can compound when they are added up to estimate total emissions.”

Instead, Michalak and her colleagues used a top-down approach.

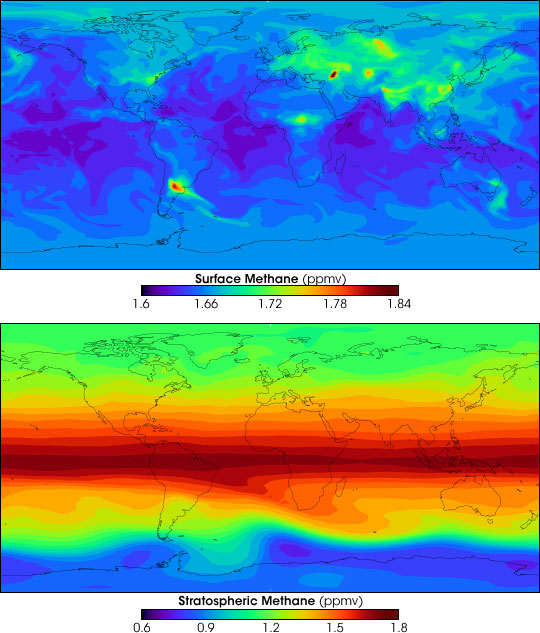

The researchers, using data collected in 2007 and 2008, combined concentrations of atmospheric methane, as measured by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Department of Energy, with meteorological data of temperatures, wind, and other factors that could influence the methane’s atmospheric movements. They entered this combination in their computer model and essentially ran its statistical algorithms in reverse to trace the methane to its origins.

Looking at the country as a whole, the scientists found that actual methane emissions were 50 percent higher than the EPA inventories predicted.

The scientists paired regional methane emissions with activity plots—farming, fossil fuel production, etc.—to identify sources that were previously undervalued. In the south central United States, for instance, total emissions are 2.7 times higher. Livestock, predominantly cattle, was a primary contributor, via animal flatulence (true!) and manure. Emission from oil and gas production and refining was 4.9 times higher than the inventory would suggest for this region.

Such significant increases could suggest areas and practices that could benefit from improved regulation and help inform national and state greenhouse gas reduction strategies, Michalak and her colleagues say.

Their study was published last week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Image: Methane distribution, NASA