Science News

The Paris Agreement - Success!

“Ice sheets are starting to melt, coastlines are flooding from rising seas, and some types of extreme weather are growing worse,” Justin Gillis wrote in the New York Times this weekend. “Yet some of the consequences of an overheated planet might be avoided, or at least slowed, if the climate deal succeeds in reducing emissions.”

At 7:30 p.m. Central European Time on Saturday, nearly 200 nations came to an agreement to fight global warming. The significant Paris Agreement will limit temperatures to a 1.5° Celsius rise through a reduction of greenhouse gas emissions over the next few decades.

How will we achieve this? According to the new treaty, by reducing the use of fossil fuels, committing to renewable energy, spending money to protect existing forests and to grow new forests as carbon sinks, and sharing the costs between developed and developing countries.

“Expert reviewers have praised the newest, final draft agreement from the COP21 talks in Paris as scientific, balanced, and—perhaps most importantly—ambitious,” Nick Stockton writes in Wired. “In all, the document appears to do something nobody thought possible, which is look out for the needs of developing countries while also sending a strong signal to investors that they should start shifting their resources to things that don’t destroy Earth.”

And according to Nature, “Never before had so many promises been put on the table—but many pledges were hedged with conditions, such as calls for financial aid to build alternative-energy plants, save remaining forests or relocate people living in harm’s way.”

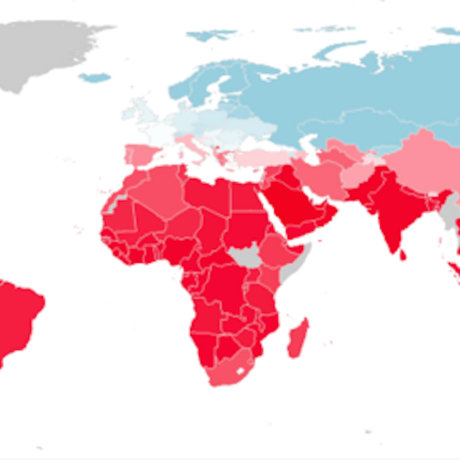

And a few more details… “[The] 1.5°C limit is reflected in the final agreement, and would require global greenhouse gas pollution to peak in 2020 and zero carbon by 2050,” says Scientific American. But not all peaks are created equal, according to NPR, “China and India will be allowed to increase emissions for many years.”

To enforce the agreement, “Countries will also be legally required to reconvene every five years starting in 2023 to publicly report on how they are doing in cutting emissions compared to their plans. They will be legally required to monitor and report on their emissions levels and reductions, using a universal accounting system,” writes the New York Times. But Nature says that the accounting system allows for some flexibility for the poorest nations, “that have little capacity” to report and verify emissions.

Christopher B. Field, a scientist with Carnegie Institution’s Department of Global Ecology told the New York Times, “I think this Paris outcome is going to change the world… We didn’t solve the problem, but we laid the foundation.”