Back-to-School has arrived on the calendar for the children of San Francisco and one of the men they – and I am sure their parents - can thank for that privilege was one of the seven founding fathers of the California Academy of Sciences. He was Colonel Thomas J. Nevins, the first Superintendent of Schools for San Francisco.

Thomas Nevins arrived during the Gold Rush in 1850 from New Hampshire and, as a lawyer, he drafted the first public school law for the growing city of San Francisco.

In 1851 he was hired to serve as the first Superintendent of the Free Common [public] Schools. In that year, the city had levied taxes to maintain seven school districts.

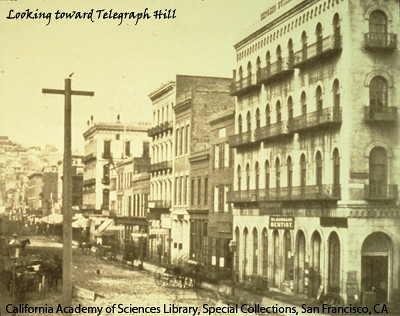

After their first meeting in April of 1853, the then California Academy of Natural Sciences members met in the office of Colonel Nevins at 622 Clay Street. Here they kept their library and their expanding ‘cabinet of specimens’. Every Monday evening by the light of tallow candles, the members read and discussed their scientific papers.

Dedicated to this infant organization, Nevins took on the role of Treasurer, the Second Vice Presidency, and the Librarian, as well as being a member of the Publication and Proceedings Committees. He was also on the committee that drafted our constitution. Later he would be made the Recording Secretary and be honored as a life member.

At the time of these first meetings of the Academy, Nevins was also actively advocating for the addition of a high school into the common school’s system. After three years, he convinced the city to establish this school. [This first high school west of the Mississippi was originally located on Powell Street and is the predecessor of today’s Lowell High School.]

While planning the new Academy after its destruction in the Earthquake of 1906, the Director, Barton W. Evermann, also actively advocated for a place for youth education in the planning for the new museum. In the revised Constitution of 1930, high school students could become active members of the Academy. [Membership at that time was an elected privilege.] The Student Section was very active in the 1940’s when teachers were hired and field trips were taken. They had their own meeting room where they could hear lectures and participate in discussions. And as scientist-in-training, they also published their own research in a newsletter.

Each Education Department program since the years of the Student Section, every Bay Area classroom field trip to our museum, and today’s Naturalist Center programs, all continue these early commitments to education by Nevins and Evermann.

Karren Elsbernd - Library Assistant for Archives and Digital Collections