Antarctic Bookshelf 6: The Heart of the Antarctic by Ernest Shackleton

"Men go out into the void spaces of the world for various reasons. Some are actuated simply by a love of adventure, some have a keen thirst for scientific knowledge, and others again are drawn away from the trodden paths by the 'lure of little voices,' the mysterious fascination of the unknown. I think that in my own case it was a combination of these factors that determined me to try my fortune once again in the frozen south… The Discovery expedition [1901-1903] had brought back a great store of information, and had performed splendid service in several important branches of science. I believed that a second expedition could carry the work still further." These are the opening lines of The Heart of the Antarctic, Sir Ernest Shackleton's chronicle of the British Antarctic Expedition of 1907-1909. The Nimrod Expedition, as it is commonly called, was Shackleton's second of four voyages to Antarctica and his first as Commander. Unlike the more famous Endurance Expedition to follow, the Nimrod endeavor was never novelized. Its descriptions remain penned solely by Shackleton and his crew who kept daily diaries throughout the journey, recording everything from scientific surveys and food consumption to their states of mind and the weather. The Heart of the Antarctic is informed by these writings, providing a thorough account of the voyage and great insight into the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

"Men go out into the void spaces of the world for various reasons. Some are actuated simply by a love of adventure, some have a keen thirst for scientific knowledge, and others again are drawn away from the trodden paths by the 'lure of little voices,' the mysterious fascination of the unknown. I think that in my own case it was a combination of these factors that determined me to try my fortune once again in the frozen south… The Discovery expedition [1901-1903] had brought back a great store of information, and had performed splendid service in several important branches of science. I believed that a second expedition could carry the work still further." These are the opening lines of The Heart of the Antarctic, Sir Ernest Shackleton's chronicle of the British Antarctic Expedition of 1907-1909. The Nimrod Expedition, as it is commonly called, was Shackleton's second of four voyages to Antarctica and his first as Commander. Unlike the more famous Endurance Expedition to follow, the Nimrod endeavor was never novelized. Its descriptions remain penned solely by Shackleton and his crew who kept daily diaries throughout the journey, recording everything from scientific surveys and food consumption to their states of mind and the weather. The Heart of the Antarctic is informed by these writings, providing a thorough account of the voyage and great insight into the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.  Shackleton arranges the book in chronological order. The trip begins with its inception and funding in England, the securing of supplies in Norway, and the vessel Nimrod's transit to Lyttelton, New Zealand where dogs, ponies, and final provisions are brought on board. On arriving off Antarctica's shores in January 1908, the company of fifteen men established their winter quarters at the nearest suitable landing site, Cape Royds on McMurdo Sound. The team's hut, a prefabricated structure measuring 627 square feet, was constructed shortly upon arrival. It included a kitchen area, darkroom, laboratory, storage section, and living space consisting of several two-person cubicles that acquired addresses such as "No. 1 Park Lane," "The Gables," and "The Rogue's Retreat." It was in the cramped quarters of the "The Rogue's Retreat" that crew members Ernest Joyce and Frank Wild oversaw the production of Aurora Australis, the "first book ever written, printed, illustrated and bound in the Antarctic," as Shackleton writes. (More about Aurora Australis in my next Antarctic Bookshelf post.)

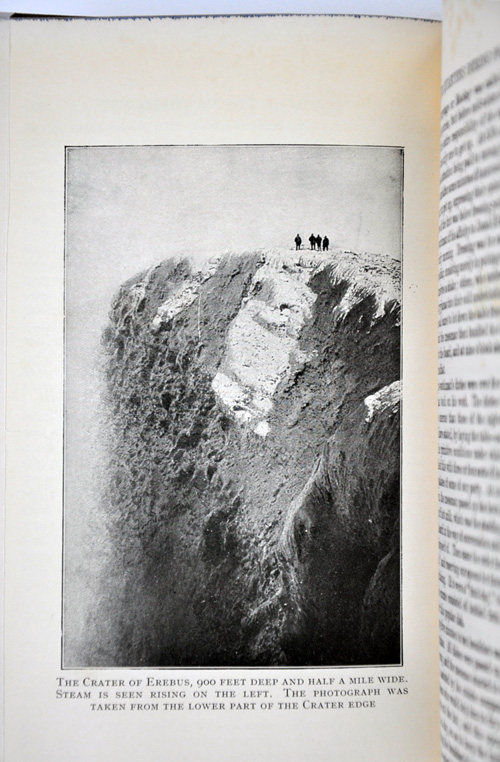

Shackleton arranges the book in chronological order. The trip begins with its inception and funding in England, the securing of supplies in Norway, and the vessel Nimrod's transit to Lyttelton, New Zealand where dogs, ponies, and final provisions are brought on board. On arriving off Antarctica's shores in January 1908, the company of fifteen men established their winter quarters at the nearest suitable landing site, Cape Royds on McMurdo Sound. The team's hut, a prefabricated structure measuring 627 square feet, was constructed shortly upon arrival. It included a kitchen area, darkroom, laboratory, storage section, and living space consisting of several two-person cubicles that acquired addresses such as "No. 1 Park Lane," "The Gables," and "The Rogue's Retreat." It was in the cramped quarters of the "The Rogue's Retreat" that crew members Ernest Joyce and Frank Wild oversaw the production of Aurora Australis, the "first book ever written, printed, illustrated and bound in the Antarctic," as Shackleton writes. (More about Aurora Australis in my next Antarctic Bookshelf post.)  In early March 1908, six of the team members undertook the first ever ascent of Mount Erebus, the world's southernmost active volcano. At 12,450 feet in elevation, the climb took seven days to complete. The group braved gales, injuries, and shortages, calling for resourcefulness and improvisation. "They were now very thirsty," Shackleton writes, "but they found that if they gathered a little snow, squeezed it into a ball and placed it on the surface of a piece of rock, it melted at once almost on account of the heat of the sun and thus they obtained a makeshift drink." Eventually five of the men attained the summit, the sixth having been incapacitated by frostbite. At the crater's edge, meteorological experiments were carried out, surveys were made, and geological specimens were retrieved. The photo above was taken by Douglas Mawson, the expedition's physicist. The trek report describes the scene: "We stood on the verge of a vast abyss, and at first could see neither to the bottom nor across it on account of the huge mass of steam filling the crater and soaring aloft in a column 500 to 1000 ft. high. After a continuous loud hissing sound, lasting for some minutes, there would come from below a big dull boom, and immediately great globular masses of steam would rush upwards to swell the volume of the snow-white cloud which ever sways over the crater. This phenomenon recurred at intervals during the whole of our stay at the crater. Meanwhile, the air around us was extremely redolent of burning sulphur. Presently a pleasant northerly breeze fanned away the steam cloud, and at once the whole crater stood revealed to us in all its vast extent and depth. Mawson's angular measurement made the depth 900 ft. and the greatest width about half a mile."

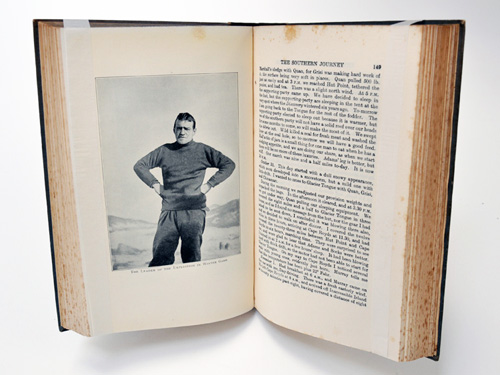

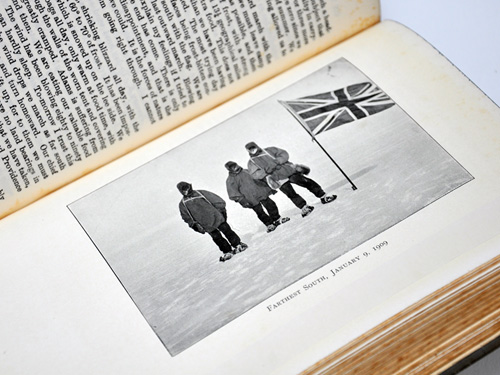

In early March 1908, six of the team members undertook the first ever ascent of Mount Erebus, the world's southernmost active volcano. At 12,450 feet in elevation, the climb took seven days to complete. The group braved gales, injuries, and shortages, calling for resourcefulness and improvisation. "They were now very thirsty," Shackleton writes, "but they found that if they gathered a little snow, squeezed it into a ball and placed it on the surface of a piece of rock, it melted at once almost on account of the heat of the sun and thus they obtained a makeshift drink." Eventually five of the men attained the summit, the sixth having been incapacitated by frostbite. At the crater's edge, meteorological experiments were carried out, surveys were made, and geological specimens were retrieved. The photo above was taken by Douglas Mawson, the expedition's physicist. The trek report describes the scene: "We stood on the verge of a vast abyss, and at first could see neither to the bottom nor across it on account of the huge mass of steam filling the crater and soaring aloft in a column 500 to 1000 ft. high. After a continuous loud hissing sound, lasting for some minutes, there would come from below a big dull boom, and immediately great globular masses of steam would rush upwards to swell the volume of the snow-white cloud which ever sways over the crater. This phenomenon recurred at intervals during the whole of our stay at the crater. Meanwhile, the air around us was extremely redolent of burning sulphur. Presently a pleasant northerly breeze fanned away the steam cloud, and at once the whole crater stood revealed to us in all its vast extent and depth. Mawson's angular measurement made the depth 900 ft. and the greatest width about half a mile."  Erebus, however, was a light jog compared to the real work that lay ahead. (The ascent was in fact an unscheduled endeavor, proposed by Shackleton during a period of down-time "to seek some outlet for our energies that would be useful in advancing the cause of science, and the work of the expedition.") Shackleton's three major objectives were attempted by organizing the company into three sledging parties. The first of these, the Southern Party, set their sights on reaching the Geographic South Pole. Led by 'The Boss' himself, this group set off in October 1908, trekking to within 100 miles of their destination. Along the way they crossed and charted much new terrain, notably that of the Great Ice Barrier (now known as the Ross Ice Shelf), the Trans-Antarctic mountain range, the mighty Beardmore glacier which they named after their principal benefactor, and the central polar plateau. The 73-day march was by far the longest southern polar journey to that date and a record convergence on either Pole, a feat for which Shackleton was knighted. The return voyage was no less challenging, beset by dwindling rations, severe weather conditions and the need to man-haul after losing all the ponies. Altogether the Southern Party travelled over 1,750 miles by foot and sledge. The second team, the Northern Party, was tasked with reaching the South Magnetic Pole. The three-man group departed winter quarters in September 1908, arriving at their destination in January 1909 to claim it for the British Empire. This return hike too was marred by fatigue, food shortages and severe weather, threatening to delay them from a planned rendezvous with the vessel Nimrod which had returned from New Zealand to pick the parties up. Having missed the ship's first pass of the shore, the group was spotted and retrieved by the vessel two days later. The Northern Party's mission was achieved entirely by man-hauling without dogs or ponies, led by Welsh Australian geology professor T. W. Edgeworth David who Shackleton had appointed as the Nimrod expedition's scientific director. The third lot, the Western Party, were dispatched twice. Their first job was to plant stores along the Northern Party's return path from the South Magnetic Pole. Their second operation was to explore the Ferrar Glacier, flowing from the plateau of Victoria Land across 35 miles (56 km) to McMurdo Sound. In doing so, they carried out a full geological survey in the Dry Valleys region and explored new expanses of Victoria Land. Their closest call occurred when they were back on the coast awaiting the Nimrod's arrival. The sea ice they were camping on broke loose and nearly took them out of McMurdo Sound save for a momentary brush against the shore, enabling the men to escape. After three weeks of frigid coast-side camping, they were found, rescued, and returned to New Zealand along with the rest of the company to great acclaim. In the last pages of the book, Shackleton writes about encountering the milder latitudes once more: "That was a wonderful day to all of us. For over a year we had seen nothing but rocks, ice, snow, and sea. There had been no colour and no softness in the scenery of the Antarctic; no green growth had gladdened our eyes, no musical notes of birds had come to our ears. We had had our work, but we had been cut off from most of the lesser things that go to make life worth while. No person who has not spent a period of his life in those 'stark and sullen solitudes that sentinel the Pole' will understand fully what trees and flowers, sun-flecked turf and running streams mean to the soul of a man." I can attest to that euphoric sensation following even a scant month in Antarctica. Yet if there's anything to match the experience of flora after the Ice, it is surely the experience of the Ice after flora. Shackleton likely agreed, for in five years' time he was sailing for the southern continent once more, this time at the helm of the Endurance.

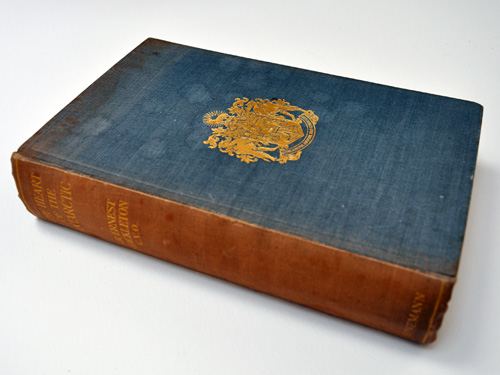

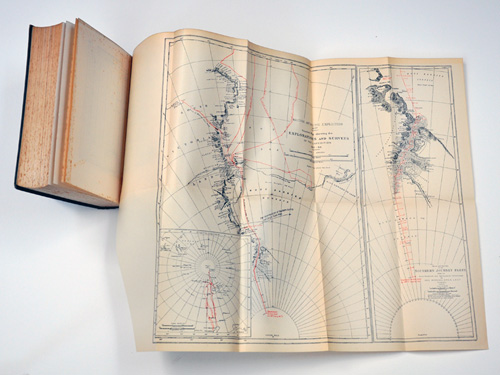

Erebus, however, was a light jog compared to the real work that lay ahead. (The ascent was in fact an unscheduled endeavor, proposed by Shackleton during a period of down-time "to seek some outlet for our energies that would be useful in advancing the cause of science, and the work of the expedition.") Shackleton's three major objectives were attempted by organizing the company into three sledging parties. The first of these, the Southern Party, set their sights on reaching the Geographic South Pole. Led by 'The Boss' himself, this group set off in October 1908, trekking to within 100 miles of their destination. Along the way they crossed and charted much new terrain, notably that of the Great Ice Barrier (now known as the Ross Ice Shelf), the Trans-Antarctic mountain range, the mighty Beardmore glacier which they named after their principal benefactor, and the central polar plateau. The 73-day march was by far the longest southern polar journey to that date and a record convergence on either Pole, a feat for which Shackleton was knighted. The return voyage was no less challenging, beset by dwindling rations, severe weather conditions and the need to man-haul after losing all the ponies. Altogether the Southern Party travelled over 1,750 miles by foot and sledge. The second team, the Northern Party, was tasked with reaching the South Magnetic Pole. The three-man group departed winter quarters in September 1908, arriving at their destination in January 1909 to claim it for the British Empire. This return hike too was marred by fatigue, food shortages and severe weather, threatening to delay them from a planned rendezvous with the vessel Nimrod which had returned from New Zealand to pick the parties up. Having missed the ship's first pass of the shore, the group was spotted and retrieved by the vessel two days later. The Northern Party's mission was achieved entirely by man-hauling without dogs or ponies, led by Welsh Australian geology professor T. W. Edgeworth David who Shackleton had appointed as the Nimrod expedition's scientific director. The third lot, the Western Party, were dispatched twice. Their first job was to plant stores along the Northern Party's return path from the South Magnetic Pole. Their second operation was to explore the Ferrar Glacier, flowing from the plateau of Victoria Land across 35 miles (56 km) to McMurdo Sound. In doing so, they carried out a full geological survey in the Dry Valleys region and explored new expanses of Victoria Land. Their closest call occurred when they were back on the coast awaiting the Nimrod's arrival. The sea ice they were camping on broke loose and nearly took them out of McMurdo Sound save for a momentary brush against the shore, enabling the men to escape. After three weeks of frigid coast-side camping, they were found, rescued, and returned to New Zealand along with the rest of the company to great acclaim. In the last pages of the book, Shackleton writes about encountering the milder latitudes once more: "That was a wonderful day to all of us. For over a year we had seen nothing but rocks, ice, snow, and sea. There had been no colour and no softness in the scenery of the Antarctic; no green growth had gladdened our eyes, no musical notes of birds had come to our ears. We had had our work, but we had been cut off from most of the lesser things that go to make life worth while. No person who has not spent a period of his life in those 'stark and sullen solitudes that sentinel the Pole' will understand fully what trees and flowers, sun-flecked turf and running streams mean to the soul of a man." I can attest to that euphoric sensation following even a scant month in Antarctica. Yet if there's anything to match the experience of flora after the Ice, it is surely the experience of the Ice after flora. Shackleton likely agreed, for in five years' time he was sailing for the southern continent once more, this time at the helm of the Endurance.  The Heart of the Antarctic, Being the Story of the British Antarctic Expedition 1907-1909 was first published in two volumes by William Heinemann, London, in November 1909. Heinemann also issued a three-volume deluxe edition of 300 numbered vellum-bound copies that year. This scarce set's third volume, titled The Antarctic Book, includes Shackleton's poem "Erebus" and Mawson's fiction piece "Bathybia," drawn from the pages of the expedition's home-grown Aurora Australis. It also includes etchings by expedition artist George Marston. Significantly, this third volume features on two leaves the hand-written signatures of all fifteen shore party members; the British participants on one side and the Australian participants on the other. Pictured in the photos above is the New Popular Edition published by Heinemann in May 1932. It condensed Shackleton's text into a single volume, offering the book to a larger public at an affordable price.

The Heart of the Antarctic, Being the Story of the British Antarctic Expedition 1907-1909 was first published in two volumes by William Heinemann, London, in November 1909. Heinemann also issued a three-volume deluxe edition of 300 numbered vellum-bound copies that year. This scarce set's third volume, titled The Antarctic Book, includes Shackleton's poem "Erebus" and Mawson's fiction piece "Bathybia," drawn from the pages of the expedition's home-grown Aurora Australis. It also includes etchings by expedition artist George Marston. Significantly, this third volume features on two leaves the hand-written signatures of all fifteen shore party members; the British participants on one side and the Australian participants on the other. Pictured in the photos above is the New Popular Edition published by Heinemann in May 1932. It condensed Shackleton's text into a single volume, offering the book to a larger public at an affordable price.