Science News

Familiar Vesta

October 5, 2011

Vesta, “the smallest terrestrial planet” in our solar system, took center stage yesterday at a joint meeting of the American Astronomical Society’s Division of Planetary Sciences and the European Planetary Science Congress in Nantes, France.

Vesta is actually an asteroid, one of the largest in the solar system. Since mid-July, NASA’s Dawn mission has been orbiting and imaging what is possibly the oldest planetary surface in the solar system.

The rather potato-shaped Vesta measures about 578 by 560 by 458 kilometers (359 by 348 by 285 miles): “too small and odd-shaped to qualify as a dwarf planet,” according to Scientific American. Yet scientists are astounded at its planet-like features.

“We are learning many amazing things about Vesta, which we call the smallest terrestrial planet,” said Chris Russell, the Dawn Principal Investigator. “Like Earth, Mars, Venus and Mercury, Vesta has ancient basaltic lava flows on the surface and a large iron core. It has tectonic features, troughs, ridges, cliffs, hills and a giant mountain.”

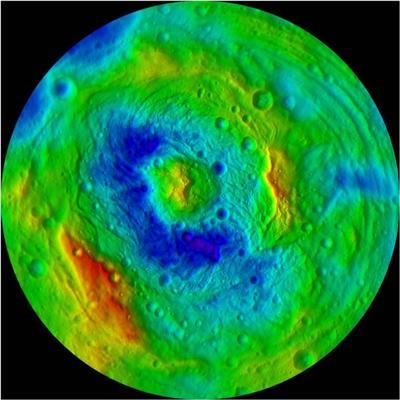

That giant mountain could be an understatement! At 20 kilometers in height (over 65,000 feet), “The south polar mountain is larger than the big island of Hawaii, the largest mountain on Earth, as measured from the ocean floor,” Russell explained. “It is almost as high as the highest mountain in the solar system, the shield volcano Olympus Mons on Mars.”

The surface of Vesta shows the ravages of time. Many more craters are seen in the northern hemisphere than the southern because an enormous impact altered the earlier cratering record in the south. (Check out the familiar-looking “Snowman” crater on Discover’s Bad Astronomy blog.) “The team is now measuring the craters, identifying ridges, hills and lineations to have the sunlit surface totally mapped by the end of the year,” said Russell.

Astronomers find the difference in the cratering between the two hemispheres quite striking (so to speak). By counting the number of craters per unit area in different regions, astronomers can estimate the relative ages of the different terrains. Preliminary results of these crater age dates indicate much younger ages for areas in the south versus the north, as young as 1-2 billion years old. So far, the oldest ages, in the northern hemisphere, are younger than 4 billion years old—an unexpected result given that meteorites from Vesta have ages of 4 billion years! However, more detailed data will eventually allow refinement of the crater counts, and the assumptions about how the impact flux (or rate of impacts) decreases with time will be evaluated, so the absolute ages are preliminary.

Scientific American reports on the importance of studying Vesta:

The asteroid made a particularly interesting target for Dawn because the space rock carries evidence of the history of much of the solar system as well. Vesta-derived meteorites that landed on Earth allowed planetary scientists to measure the asteroid’s age in the laboratory, showing that it is one of the oldest large bodies in the solar system… As such, Vesta provides a valuable lab for studying the materials and processes that formed the planets during the first millions of years in the early solar system.

Image: NASA/JPL/Dawn