Science News

Updates from the Rosetta Mission

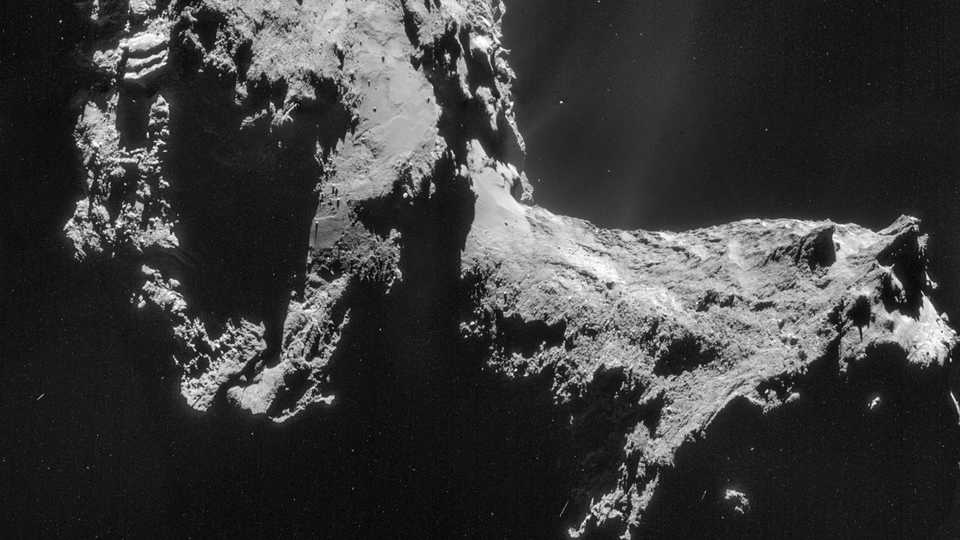

Yesterday a group of scientists gave an update on the Rosetta mission at the American Geophysical Union (AGU) meeting in San Francisco. The gist of it? After sending a spacecraft on a 10-year journey to a faraway comet and dropping a lander on its surface, scientists have determined that the chosen Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko is cold, hard, and stinky, and most certainly a treasure chest of data.

Why so much attention to this oddly shaped comet? Claudia Alexander of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) explained that 67P is likely an object from the Kuiper belt, a region in space extending out from Neptune’s orbit, containing thousands of mostly icy bodies that are considered dusty remnants from the birth of our own solar system. The theory is that billions of years ago, Neptune and Uranus shifted their orbits, causing a cataclysmic event that scattered tiny, water-rich asteroids and comets throughout the Solar System. (Some of them could have brought water to Earth!) However, the Kuiper belt remained largely unchanged, and 67P could hold some evidence of this water and early Solar System.

Kathrin Altwegg is the principal investigator of ROSINA, a suite of instruments on the Rosetta orbiter, and agrees that this comet is an excellent choice to study. ROSINA has examined the comet since August, and continues to take measurements as the spacecraft orbits. The data collected have revealed many exciting aspects of the large dusty and icy rock: its rotation gives it a 12.4-hour day and its chemical composition makes the comet pretty stinky. She hopes with more analysis, the team can uncover further mysteries— do the differing chemical signatures indicate that the comet was once two objects? Are there more organics and noble gases on the comet?

Despite the bumpy landing, or maybe even because of it, Jean-Pierre Bibring, lead scientist for the Philae lander team, says that so far, the first in-situ comet exploration has been a success. And he thinks so even though Philae is currently hibernating due to lack of sunlight. Bibring said that currently the lander, likely situated between two large rocks, probably receives about four-and-a-half hours of sunlight, and it needs about six to operate. He is very hopeful that by February (at the earliest) and May (at the latest) it will get enough light to come out of hibernation.

That is, if Philae can survive the cold over the next several months. The lander’s instruments were designed to handle temperatures as low as –80° Celsius, and the camera can function at temperatures down to –150° Celsius, but it’s difficult to determine exactly how cold its location is, and how much colder it will get.

Obviously, there’s much unknown about the current location of the lander on the comet’s surface, or its orientation after such a bouncy landing. But we may have a Christmas present, Matt Taylor, Rosetta project scientist, explained. Images taken by the Rosetta orbiter of the assumed location on December 12, 13, and 14 should come down to Earth (data have to travel half a billion kilometers!) in the next week to reveal Philae’s whereabouts.

The bounce did reveal that the comet’s surface is much harder than originally thought. Taylor notes that, although the team plans to review why the harpoons did not work, it may end up that it’s fortunate that they did not deploy. Should the harpoon have made contact with the hard surface, they could have ejected Philae back into space.

With the potential awakening of Philae and optimistic fuel reserves on Rosetta, the team hopes to extend the mission well into 2016. So stay tuned for news along the way…

Image: ESA